What drives success among Asian Americans?

UC and Harvard lawsuits prompt reflection

In some ways, Cambodian-American Boyle Heights resident Chrissna Sin’s life has been prescribed.

He would not work in high school, even though it meant he couldn’t afford spending money to join sports leagues.

He would be a business administration major, eventually becoming an accountant, nurse or businessman – professions that have no shortage of jobs.

“My parents would tell me to graduate quickly and get a job that is financially sustainable. I was told not to focus on work and to make studying a priority for success in school,” said Sin.

Sin said he doesn’t begrudge the assertive parenting because, ultimately, it was their way of ensuring he succeeded: “The morals my parents implemented have made me the person I am today.”

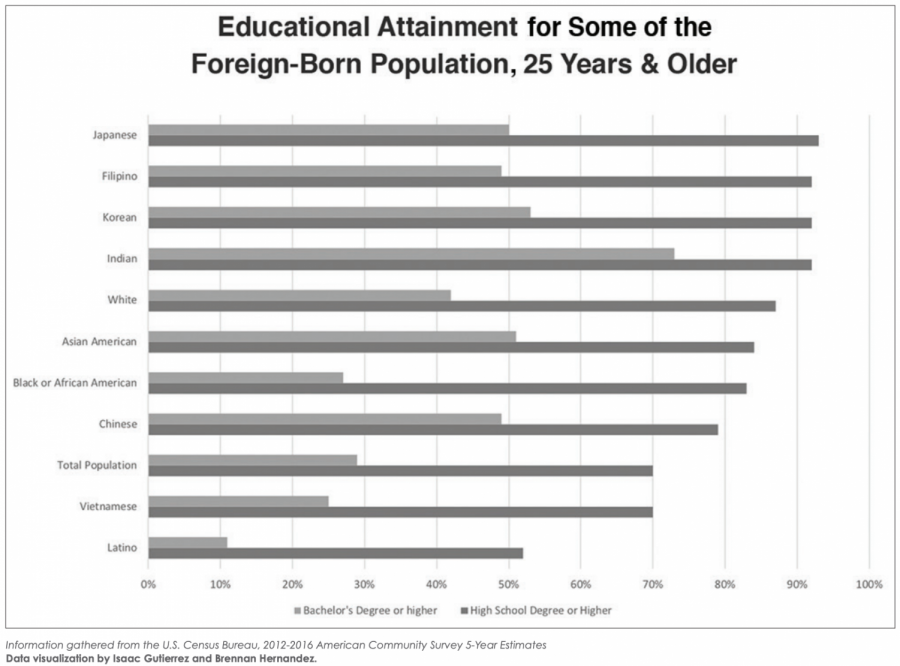

Lawsuits against the University of California system and Harvard alleging discrimination against Asian Americans in the admissions process have prompted community members in Los Angeles County – which has the largest Asian American population in the country – to ask how it came to be that those of Asian descent have the highest educational achievement of all ethnic and racial groups in the country. For instance, 53 percent of Asian Americans have a bachelor’s degree or higher, compared to 36 percent for white folks, 23 percent for Black people and 15 percent for the Latinx community, according to a 2015 analysis done by the Pew Research Center.

While Asia is a diverse continent of 48 countries, making up about 60 percent of the world’s population, a combination of real and perceived cultural commonalities among Asian Americans – such as an emphasis on effort and academic achievement – may contribute to the academic success of many in the community, according to experts.

A 2014 study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences tested socio-demographic characteristics, innate cognitive abilities and work ethic to determine what led to an achievement gap between white and Asian American students. It found only the latter contributed significantly to achievement.

Sin said the high expectations within some segments of the culture can also be a dark side: “For some families, these expectations may be toxic because of the comparison between other Asian families” or children may not pursue jobs they may be better suited for in the arts, for instance, because of stigmas around those professions.

With 1.4 million people, Asian Americans make up 14 percent of Los Angeles County – more than any other county in the United States, according to 2018 data from the U.S. Census Bureau.

Growing up in Chinatown, Wesley Zhang said he noticed homogeneity in many of his friends’ and neighbors’ interests. For instance, school was emphasized while sports and extracurriculars were considered secondary.

“Most of my friends I lived near and went to school with dealt with similar expectations to succeed academically and even sought similar hobbies like the piano,” said Zhang, who was tabling in Cerritos for his Bible study program. “Some expectations in the Asian community is to go to a good school and succeed in a prestigious job.”

Growing up first-generation, Zhang faced major cultural differences, including language issues since he and his family spoke Mandarin at home.

Wesley said his parents nurtured his interest in science as a child by including him in Science programs like Team Science Camp.

That led him to pursue biochemistry as a major in college. He said the hard work and late nights studying were worth it when he saw how happy his family was when he received his high school diploma. He felt thankful “having the ability to represent my culture.”

For some Asian American families, the drive to survive and succeed as new immigrants is replaced as they assimilate.

For instance, Brian Yamamoto, a Monterey Park resident and auto mechanic, said his parents raised him to pursue what made him happy and were less concerned about traditional measures of success.

“I compared my way of life to some of the Asians I knew, and I think I had it easier than them,” Yamamoto said. “I was able to enjoy my childhood. That’s something I know a lot of my peers weren’t able to do.”

Growing up, he said he didn’t feel immense pressure to focus on school and become overly successful. He attributes that to his parents being first-generation Los Angeles residents. Yamamoto’s grandparents immigrated from Japan and his parents were born and raised locally.

As a young Japanese American growing up in Southern California during the 1980s, he said he felt secluded due to a small Asian community in his area: “All my friends were Latino or White; there were some Asians but we were outnumbered, for sure.”

Yamamoto turned to sports for camaraderie. “I played basketball and football, but nothing compared to baseball for me. My teammates really felt like brothers,” said Yamamoto.

Yamamoto, 42, still plays baseball in a Sunday-night league. He said he hopes to raise his two kids the same way he was brought up: Enjoying life.

Community News reporters are enrolled in JOUR 3910 – University Times. They produce stories about under-covered neighborhoods and small cities on the Eastside and South Los Angeles. Please email feedback, corrections and story tips to [email protected].