Deborah Glover wants her own space, but she hasn’t had a permanent one in over a decade.

She has dreams of having a house one day. She’s awaiting potentially moving into a duplex, which she says is a “step up” from her current living situation: a temporary spot at a fleabag hotel near Skid Row.

At a food distribution event late last fall, Glover stood patiently in line waiting to move forward. About 100 people stood ahead of her, and about 25 behind her.

Men yelled at each other nearby, but Glover spoke to UT Community News over the noise: “I like to be open and free [and] distant from people.”

Los Angeles’ Skid Row may be open and free but perhaps not in the liberating way Glover implied. Driving down Fifth Street or Maple Avenue, the view is bleak: streets lined with tents, littered with debris and the main pops of color are blue tarps and graffiti.

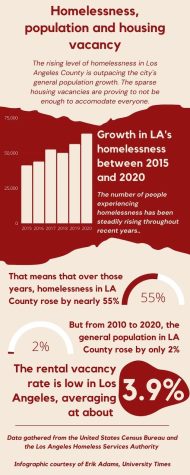

It’s nothing new to anyone living in or near Los Angeles. Homelessness grew disproportionately to the city’s general population growth. Despite only a 2% increase in Los Angeles County’s overall population between 2010 and 2020, the homeless population has increased by 55% in about half of that amount of time, according to U.S. Census and Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority data.

Dulce Vasquez, who is running for Los Angeles City Council’s District 9 spot, said there are several reasons why the city’s homeless population is growing.

“At the forefront is housing and housing unaffordability,” said Vasquez. “At every single level, we need more housing.”

The lack of mental healthcare treatment for drug addiction is also a contributing factor, she added.

“There are many different levels of homelessness, and some of it that we can’t even see,” she said. “The couch surfing, the families living out of their cars, that often [goes] uncounted.”

Glover, was born in Shreveport, Louisiana, and raised in Compton, California, experienced some of that.

She moved around in Los Angeles and the Inland Empire before ultimately beginning life on Skid Row in 2009.

“I was in a program [on Skid Row], and they just took me off in like three months to make room for more people,” she said.

With the help of an acquaintance she’d met, Glover then moved to a house in the city of Perris in Riverside County — somewhere she knew little about.

She said it was “his grandmother’s house…It was horrible. He moved some inmates in there, people who were fresh out of prison, and they were threatening me.”

From there, Glover eventually moved into her brother’s home in nearby Moreno Valley while she attended Moreno Valley College.

“I was with him for two years,” she said. “I was on my way to finish getting my A.A. degree.”

That chapter came to a close when hardship fell upon Glover’s brother.

“He was married to his wife of 30 years who died of bone cancer,” she explained. Her brother had been using drugs, and eventually Glover left his residence and became homeless again. She is currently staying at the Baltimore Hotel near the Los Angeles Mission.

About 4,700 people are living on Skid Row with roughly 2,100 of them being unsheltered, according to the Los Angeles Homeless Service Authority’s 2020 statistics. The 2020 total increased by about 20% compared to 2019’s data.

Glover listed “despair” and many people being “unhappy with how things are in the United States of America” as factors that put people on the street. “[America’s] always out helping other countries, but they…do nothing for the American citizens in this country,” she said.

“We don’t make enough income to pay the rent today,” said Erlinda Medina, another local woman in line at the Mission while sporting a mask with the words “I [heart] America” on it. “The cost of living is extremely high… I don’t think [we] really want to be here. This is not life for us.”

Medina explained the possible misconceptions of people experiencing homelessness on Skid Row.

“I think we all have our own problems, our own situations, and it’s very complicated,” she said. “Even if you have a job, they don’t give you benefits, not enough hours and not enough income. So you have to get two or three jobs…and make it right. You’re just getting run down.”

Medina feels that the pipeline in place for the shelters is ineffective. “You leave one situation to get into another bad situation, and that’s not the way to go at this age,” she said.

Vasquez believes the housing issue is more complicated than simply filling up vacant homes with the city’s homeless residents. L.A.’s rental vacancy rate is low compared to some other big cities with its number sitting at about 3.9% over the last six years. Other densely populated places such as the Bay Area and New York’s metropolitan area have vacancy rates averaging about 4.9% and 4.7% respectively, and some other large cities’ rates go into double digit percentages.

“We have to think about what type of units those are,” Vasquez said about the vacant spaces. She said sees “plenty of homes for sale” but “a healthy vacancy rate is good; If you want to move locations, or you get a job or a promotion and you want a nicer apartment, you should be able to find that.”

“We have the lowest vacancy rate in the country, and we still have this conversation around, ‘Oh, we have 70,000 units available. We can house everyone,’” Vasquez continued. “I don’t think that’s what we should be focusing on. I think we should be focusing on building more housing.”

Despite the growing crisis, hope is not lost.

“It’s been a struggle, but I just keep the faith that [God’s] watching over me, and he’s always above me,” Glover said. “No matter what I’m going through, he has a plan for me. That’s what I believe.”

Medina agrees: “We have faith and hope that there will be a change eventually.”

But “life goes on, right?” Medina asked rhetorically. “Take a deep breath. But you may want to take a deep breath somewhere else because it’s very rich in aromas here,” she joked, referring to some odors in and near Skid Row. “That’s the only richness here.”