In 2014, I was studying engineering at Cypress College. I had a caring girlfriend and lived with my loving mother and older brother.

From the outside, everything seemed great. I had people around me who loved me and a future that was promising.

This is the story of how I went from that to this dark thought in the span of a few months: “Killing myself is probably the best option for me right now.”

Both my older brother and my dad were engineers so I thought the only logical move for me to make is to follow in their footsteps.

Even though the idea of becoming an engineer never excited me, I figured electronic engineering would grow on me since I took an interest in anything that had a battery in it.

That’s also what led me to pick up vaping as a pastime.

Vaping was all the craze at the time and I soon started working in this tiny vape shop in a corner plaza in Anaheim between a pizza place and salon.

After work and school is when the darker feelings would creep in. I would lay in bed while a sitcom played in the background. I’d think about school and what homework I had to do the next day. Next thing I knew, my thoughts would stray to the doubts that had been haunting me.

Am I happy? Is this really what I want? Is this all life has to offer?

I’m doing everything wrong. I need to get out.

I shared a lot with my girlfriend, but I didn’t tell her about those questions. Still, she could sense something was wrong.

One day, I was stressed about school and had a panic attack. My girlfriend helped calm me down.

“The way you put yourself down is not normal and you should talk to someone about it,” I recalled her saying after that.

She believed I had a mental illness. I ignored her concerns because I thought, “How is talking to someone going to help? It’ll just be a waste of time.”

I spiraled from there. One morning, I parked my car in the student parking lot and found myself staring blankly in front of me.

I don’t want to do this. I don’t want to do any of this.

That’s when I dropped out of college. I stopped calling or talking to my friends and just decided to focus on my job at the vaping shop.

My parents were furious when they found out I’d been skipping class.

“You’re throwing your life away,” my mother, Irene Chuaseco, recalled saying.

I couldn’t admit to myself what was really going on, much less tell them.

My family was never the kind to talk about our mental or emotional health. We were the typical Asian household where any conversation I had with them always involved how well I’m doing in school and when they expect me to graduate.

Only 8.3% of Asian Americans sought mental help — compared to nearly 18 percent for the general U.S. population, according to the American Psychological Association’s website, which cites data from the National Latino and Asian American study.

I never felt comfortable even telling them about my relationships with friends or partners, let alone parts of my personality I barely understand.

Engineering never felt like the right path for me. I thought making a drastic change to my life might help. But it didn’t. If anything, new doubts arose.

What have I done? How could I have abandoned the future I had been working so hard to achieve? Am I going to be OK? Where am I going to go from here?

I had nowhere to go, no goals to work on, no ambition. I was free of lofty goals and responsibilities. But I was also lost.

So I turned to the people around me, my coworkers. They had their own problems and vices to cope with them. I was introduced to these vices.

First it was the pills. Then, it was coke. And it ended with meth. I was looking for anything that would make me feel excited or happy about anything. After about one year, I was, of course, hooked. Like a junkie on the street, I was the one who was always looking to get high.

One Friday night in 2015, my coworkers and I decided to hit up a new club that just opened up. I remember being excited because I would get to forget all my problems for a couple hours and enjoy being numb for a bit.

Later that night, I ended up getting too drunk and too high to get back into the club.

I was left behind at the parking lot across from the club, sitting on the curb of a sidewalk staring at my feet.

I heard cars go by and the crowd of people talking and laughing as they waited in line to get in and have a good time.

As I started sobering up, I contemplated the decisions I made that got me there.

It finally hit me. I had thrown my life away based on a gut feeling. The future I had planned was now gone.

I let my irrational anxiety get the best of me. I was driven by wanting to escape. I will forever be a failure. I can never go back.

“Yeah, killing myself is the best option for me,” I said to myself.

That’s when I tried to overdose.

Next thing I know, I was on a hospital bed and next to me were more empty beds. As I walked out, I saw other patients and nurses walking around a section of the hospital I’ve never seen before. It was a large and wide hallway with heavy doors on both sides that only nurses had access to. It was the psychiatric ward.

There were benches placed throughout and one patient was just standing on the corner, muttering and occasionally yelling for no reason.

“That’s our Jane Doe,” one of the nurses said to the other, as they passed me.

They told me to take a seat on one of the benches.

I was called to the doctor’s office to assess my mental health.

“You might have a mental disorder,” she said.

“What do you mean? I feel normal,” I replied.

“Wanting to kill yourself is not normal, you know. You need help.”

Until she said that, I honestly didn’t realize that my anxiety and thoughts of suicide were not normal. I had always thought that my unreasonable worries were just a part of who I am.

I thought asking for help would just be a waste of time and money. You are who you are.

When my older brother got me from the hospital, he didn’t ask what happened. We were never very close.

At home, my mom sat me down at the kitchen table and tears streamed down her face.

“Don’t ever do that again,” she said. “You know we love you no matter what, right?”

I could tell she meant that with all her heart. I also knew it would take time for me to accept those words.

That was seven years ago. Looking back, I realize that I should’ve asked for help long before dropping out of college.

About 1 in 17, or 13 million, American adults have a “serious debilitating mental illness” each year on average, according to a 2015 issue of the Oklahoma Nurse, a publication of the Oklahoma Nurses Association.

Acknowledging mental illness is the first step to healing.

It took a lot of learning and time to train myself to think, “Hey, those words of hate you say to yourself? Those are false and they’re just holding you back.”

I learned the hard way to wait and reflect before acting on my emotions in a given moment and that it’s okay to seek help. I know now that opening up to someone really does make a difference.

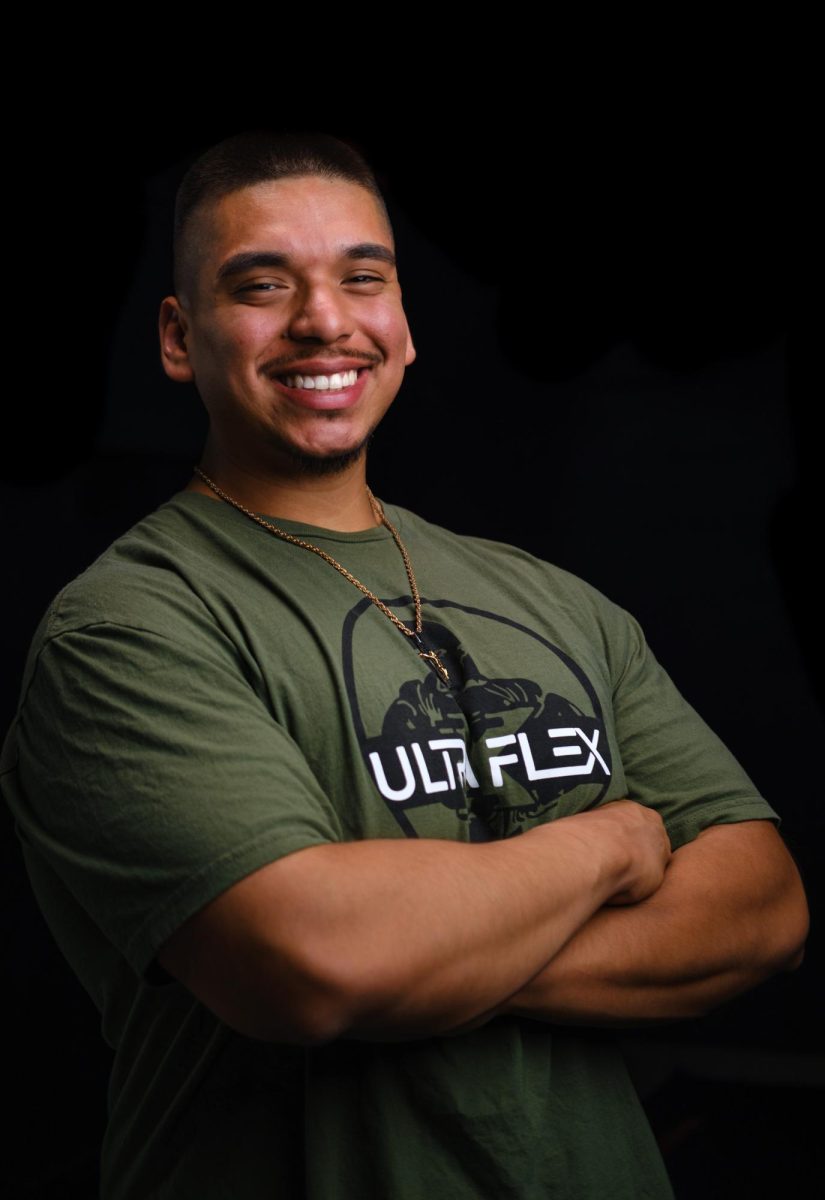

I am now a Television, Film and Media Studies major and a multimedia journalist for my student newspaper. I am on my way to pursuing a career in film because I would love to work as a video editor or a cinematographer some day. Unlike my former career path, this one excites me.

I share my story in hopes that I reach someone who may have experienced something similar and will learn from my mistakes.

If you need immediate help, you can visit mentalhealth.gov or call the 24/7 National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, 1-800-273-TALK (8255).