Brennan Hernandez

Brennan Hernandez

In 1953, Ray Bradbury published “The Murderer,” a short story in which a man is driven to technocide by the constant buzz of mobile communication technologies such as pagers, phones, and computers. Sixty-five years later, some university professors may relate to the “murderer” of Bradbury’s story.

On a Wednesday afternoon, in the John F. Kennedy Memorial Library at California State University, Los Angeles, students pore not over books, but glowing screens. With a small handful of exceptions, nearly every student stares fixedly upon a screen. But one screen reigns supreme: that of the ever-present smartphone.

Students who appear to be studying on their computers hold their phones discretely over their keyboards, or in their laps, sometimes taking more prolonged glances at their phones than at their computers.

Outside, students wander with their heads down, cellphones in hand, narrowly avoiding collisions with fellow students, benches, and railings. Their seemingly blind wandering may remind some cynical onlookers of the semi-comedic zombie hordes in George Romero’s film, Dawn of the Dead.

And cellphone use does not stop at the classroom door.

According to “The American College Student Cell Phone Survey,” both texting in class and hiding one’s cell phone usage while in class were reported by more than half of the study’s participants. However, the same study showed that a majority of students claimed that cell phones helped them use their time more efficiently.

“I don’t think of my cell phone as a distraction,” says Kaitlin, a television, film, and media student at California State University, Los Angeles. “I think of it more as a tool for me to keep up with my friends and family, get updates on current events, and stay updated on my coursework and work schedule.”

Cell Phones today are more similar to personal computers than to the comparatively simple telephones of the past. A standard iPhone, for instance, comes preinstalled with productivity applications such as Notes, Pages, Keynote, a calendar and planner, a calculator, and even a tool for scheduling the user’s sleep cycle. Certainly, the potential for productivity is present, and the aforementioned study suggests that cell phones could be used as “an effective teaching tool if harnessed wisely and creatively.”

While Kaitlin prefers not to use her phone for class notes or reading, she still says it is invaluable for other important tasks. “I have a lot on my plate this semester,” she says, “so it’s important for me to stay connected so I can make sure that I get work done and organize my time.”

Perhaps Kaitlin is an exception to the rule. But her words lend credence to the idea that cellphones can fulfill an important role in student life.

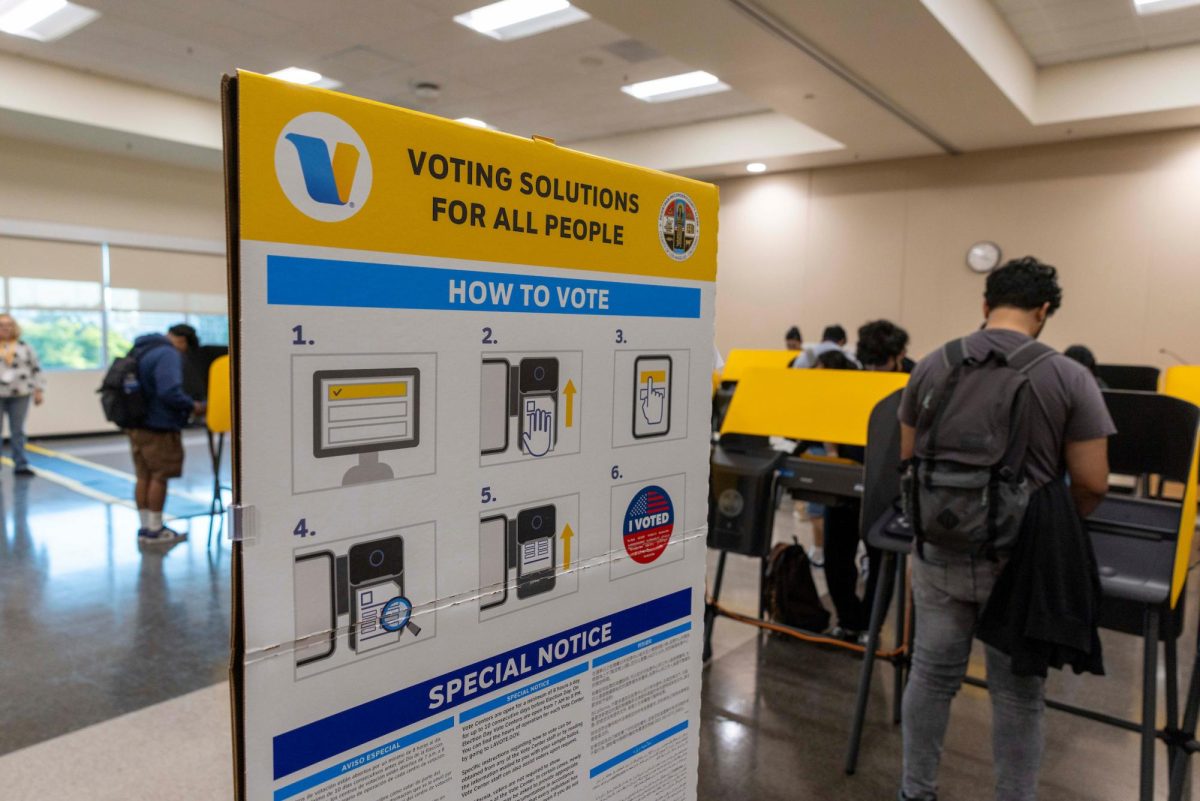

Some campuses have, in various ways, embraced cellphone usage.

SUNY Morrisville College, in New York, has taken a unique approach to cellphone regulation. There, resident students are given a cellphone and mobile plan, which are included in their student fees. Perhaps to the surprise of some professors, these student plans include “unlimited text-messaging.”

California State University, Los Angeles, tuition does not include cellphones, but the university does use text message and email alerts for emergency communications. In August, for instance, the university sent text messages instructing students on what to do and where to go during a shelter-in-place drill.

Upon closer inspection of phone use at the library, the scene is not so different from the study halls of yesteryear. One young woman copies notes from her phone, jotting them down on paper as she confers with her colleague, who, likewise, references information on her phone and her laptop. In front of them, open textbooks and notebooks share the table with open laptops.

A student walking across campus while staring at her phone may be texting a friend, or she may be responding to a time-sensitive e-mail regarding an internship opportunity. A student in the library who has been looking at his phone for hours may be watching funny cat videos, or reviewing notes for an upcoming final.

Perhaps Bradbury’s warning still holds weight. Students are bombarded by communication technology throughout the day, and it would be naive to assume that all students use their smartphones as productivity tools (or that productivity should be so heavily emphasized in general). But it would be equally naive to ignore the fact that contemporary smartphones are very capable machines, and show some promise as tools to enhance the student’s experience.