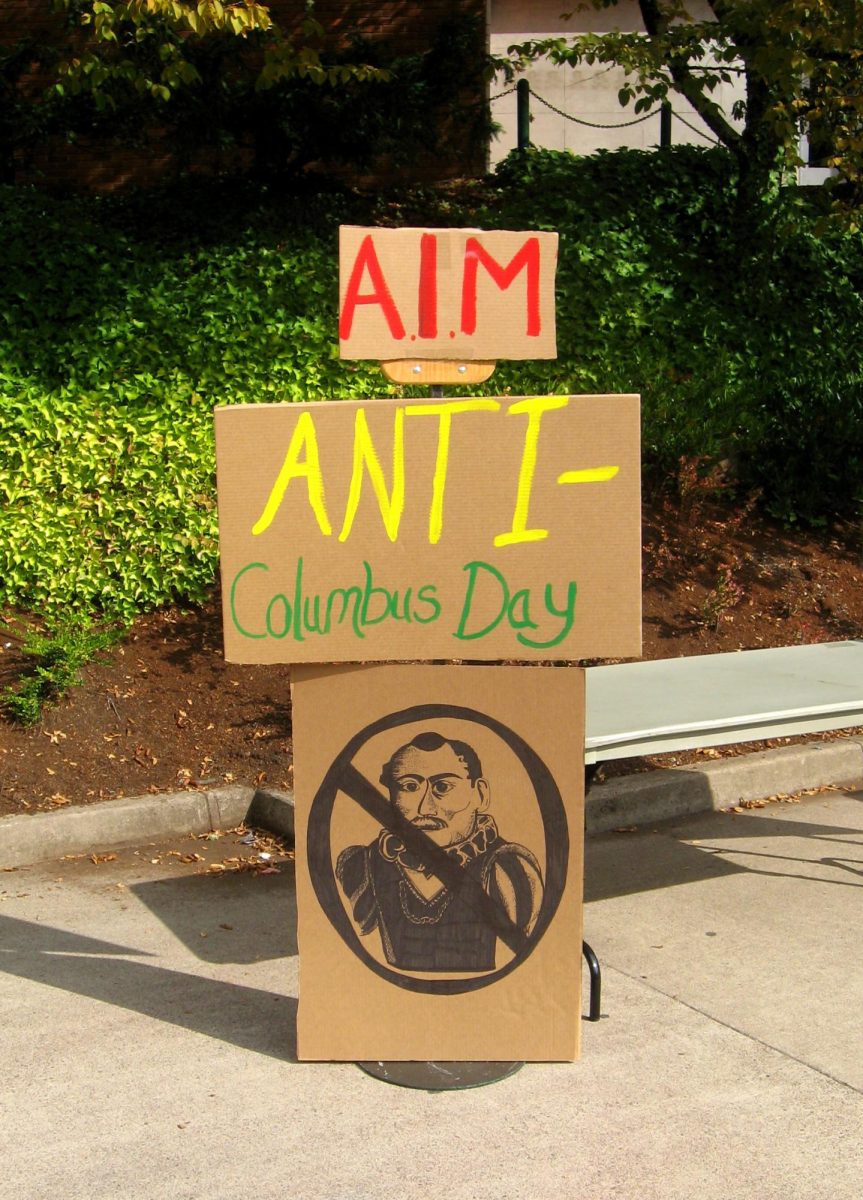

Every October, Columbus Day manages to spark controversy. Those who oppose the holiday say that Columbus was violent, did not “discover” America and that the holiday celebrates colonialism. Those concerns are not baseless, but these debates overlook something crucial: Italian Americans never celebrated Columbus for those reasons. The holiday was not created to honor one man’s actions, but instead was born from Italian American suffering; from lynching, discrimination and the fight to be treated as human in a country that exploited and rejected them.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, Italians were not considered “white.” They were denied jobs, segregated in schools, barred from neighborhoods, and even lynched. In 1891, 11 Italian men were lynched in New Orleans, one of the largest mass lynchings in U.S. history. The press did not condemn it, and instead justified it. American newspapers printed overtly hateful words.

In 1891, after the lynching, The New York Times called Sicilians “a pest without mitigation.” In 1888, The Washington Post claimed southern Italians were “an inferior race.” In 1891, The New York Times also described Italians as “filthy, lazy and dishonest” who “live like animals.”

This was not fringe rhetoric. This was mainstream American opinion.

Here is a truth that often gets ignored: Columbus Day was created in response to anti-Italian hatred. The U.S. government has openly acknowledged this.

A 2024 Presidential Proclamation states, “Columbus Day was founded by President Benjamin Harrison in 1892 in response to the horrific, xenophobic attack that took the lives of 11 Italian Americans the year before. In the face of hate, Italian Americans persisted, advancing our Nation and challenging us to live up to our highest values.”

Columbus Day was not created to glorify colonialism. It was created to confront anti-Italian violence.

The first national Columbus Day in 1892 was a one-time observance, a symbolic apology after a lynching. But discrimination continued and Italian Americans kept fighting for recognition.

In 1934, Congress passed a resolution urging the president to officially recognize Columbus Day. In 1937, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, pressured by Italian-American advocates like the Knights of Columbus, made it a federal holiday every year.

This was not a celebration of conquest. It was the first time the United States publicly said to Italian Americans: You exist. You matter. You are part of this nation.

Italian American culture has been telling this story on screen for generations. In “The Godfather Part II,” Vito Corleone arrives at Ellis Island, works tirelessly and is still treated as an outsider. In “A Bronx Tale,” the line “The working man is a sucker” reflects the exhaustion of immigrants who gave everything to America and received only disrespect. In “The Sopranos,” Tony Soprano points out that America let Italians in to “build their cities and dig their subways,” but then expected them to abandon their identity to be accepted.

These stories are not about glorifying crime. They are about survival, identity and dignity. Columbus Day emerged from that same refusal to disappear.

Some people say Columbus was violent and he was. Columbus Day was never meant to honor or celebrate the man; Italian Americans chose that name because America had already elevated it. According to Timothy Winkle for the National Museum of American History, John Pintard, an American merchant and history enthusiast, was the first to encourage honoring Columbus. In 1792, he pushed for the first public monument to Columbus in the New World. Pintard wanted to connect America to European heritage but did not want to bind it to Great Britain. In other words, the myth of Columbus was not created by Italian immigrants, it was created by Americans. Later, the Italians used that already glorified symbol in textbooks and monuments as leverage. They did not choose Columbus out of admiration, but as a strategic way to gain acceptance.

Others argue that Columbus “did not discover America.” That is historically accurate, but irrelevant to why the holiday exists.

Some insist the holiday celebrates colonialism. For Italian Americans, the creation of the holiday marked the moment that the country finally accepted them as part of its identity. It was never about conquest; it was about belonging.

Dr. Leo Killsback, a citizen of the Northern Cheyenne Nation, told CNN in 2016, “We should question why we as Americans continue to celebrate him without knowing the true history of his legacy, and why a holiday was created in the first place.”

He is right, we should question it. Because if people actually knew why the holiday was created, they would understand that Italians were not celebrating colonialism. They were responding to being targets of hate. The tragedy is that instead of learning this history, many people shame Italian Americans for celebrating a holiday thought to be about conquest. In reality, it commemorates their fight to be accepted as Americans.

Indigenous people absolutely deserve a national holiday. Their suffering is real and their history must be honored. But replacing Columbus Day with Indigenous Peoples’ Day forces two oppressed communities to compete over one date. True equity does not erase one culture to validate another. A nation capable of honoring both Martin Luther King Jr. and Cesar Chavez on separate dates is capable of honoring both Italian American and Indigenous histories. The solution is addition, not substitution.

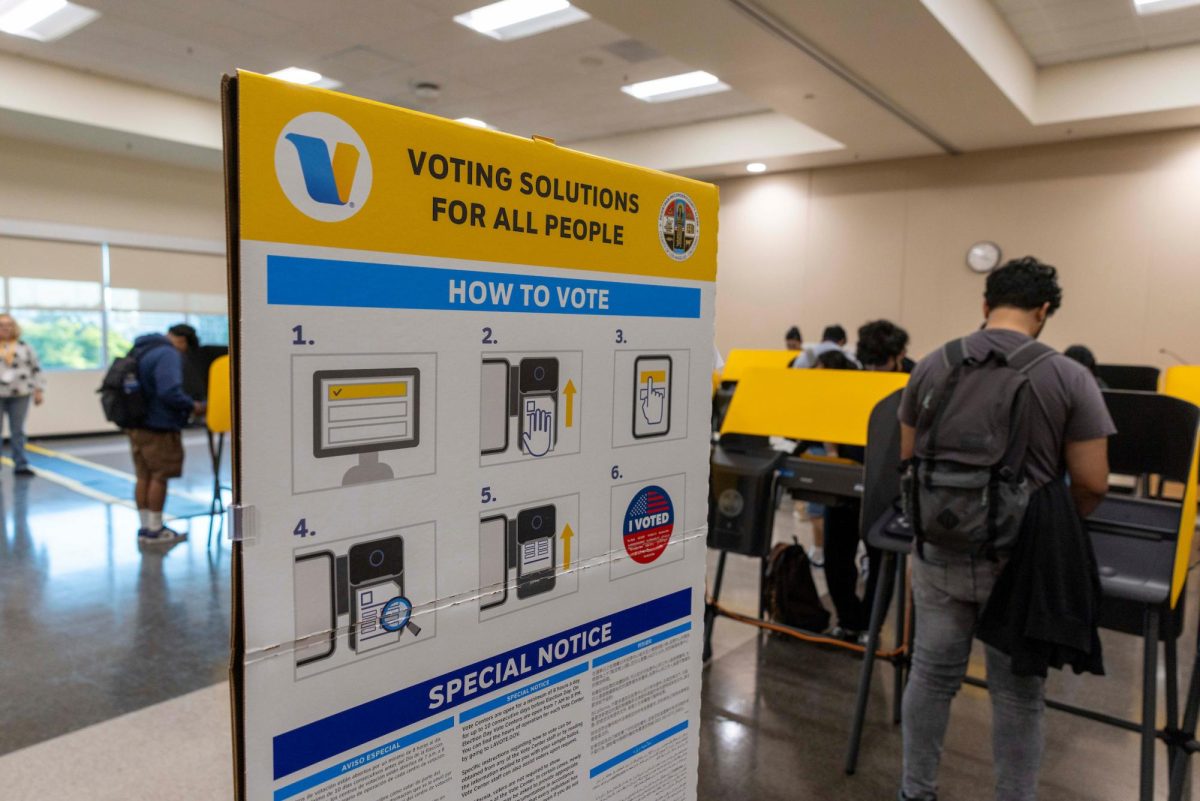

At a campus as diverse as Cal State LA, inclusion must mean making space for every community’s story, even the complicated ones. Italian American students and faculty should not be shamed for honoring a holiday that represents their family, their survival, and the fight to belong. Columbus Day is not about glorifying the past, but remembering the Italian immigrants who helped build this country and refused to disappear.

If we truly care about history and justice, we must be willing to learn the full story, not just the parts that are easy to accept. When we recognize all histories with honesty and respect, we do more than correct the past. We build a future where every community is seen.