Companies have their tactics for keeping workers from unionizing. Similarly, unions have ways of striking back.

Some say Prop. 23 represents just that.

“They’re trying to fix a non-existent problem that will cause a huge problem in the clinics,” Kim Zuber, executive director of the American Academy of Nephrology Physician Assistants (AANPA), said in a phone interview.

The Service Employees International Union-United Health Workers West (SEIU-UHW) got the measure on the ballot to, among other things, require clinics to report infection rates to the state and have an on-site physician, unless there is a legitimate shortage.

Supporters say removing blood from people during dialysis puts major pressure on people’s bodies, so having a licensed physician there would allow them to respond quickly during emergencies, according to CalMatters.

A broad coalition of healthcare groups, including the California Medical Association, the California Hospital Association, the Network of Ethnic Physician Organizations, and the Renal Physicians Association, oppose the measure — as do DaVita Kidney Care and Fresenius Medical Care, which own most of California’s for-profit dialysis clinics.

Opponents say that requiring a physician in the clinic is costly and redundant and some of the provisions, including requiring clinics to get permission from the state health department to dissolve could violate their rights as businesses and prohibiting clinics from discriminating against treating patients based on their insurance is redundant since 90% of dialysis patients are already on Medicare, according to the National Kidney Foundation.

There are more than 70,000 people in California who need dialysis three times a week to survive, according to the text of the ballot initiative.

“Our greatest concern is that it would negatively impact patient access to care…If they don’t dialyze, they die,” said Kelly Goss, of Dialysis Patients Citizens (DCP), a patient-led non-profit. Goss said the concern is that nonprofit clinics would not be able to afford having an on-site physician, which costs several hundred thousand dollars per year, so they may have to close their doors — leaving patients hanging.

Satellite Dialysis, a larger non-profit operating out of the Bay Area, could not be reached for comment; Its Facebook page, however, linked an article in opposition to Proposition 23.

Goss added that the ballot measure will also be an expensive fight. The big dialysis companies, DaVita and Fresenius spent more than $111 million to defeat 2018’s Prop. 8, which would have limited clinic profit margins, according to CalMatters.

Redundant parts of the measure include the requirement to report infections to the state: Those are already reported to the federal government and made publicly available online, opponents argue. They add that the requirement that all patients be treated no matter what kind of insurance is considered meaningless because it’s already in practice: Most people who need dialysis qualify for Medicare, even if they’re not over age 65.

Kim Zuber, executive director for the American Academy of Nephrology Physician Assistants, said her group is opposed because it’s duplicative to have a physician at clinics where registered nurses and medical directors are used to running the show: “These nurses have run their dialysis clinics for umpteen years and they’re good at it. They don’t need to be babysat.”

She added that if the bill passes, there is a risk of physicians, nephrologists and physician assistants (PAs) being pulled away from other vital work, in a pandemic, no less.

The California Labor Federation and the California Democratic Party support the measure. One of the measure’s main goals is to help drive down how much the dialysis centers charge for those few customers with private insurance.

That “actually drives up the cost of insurance for everyone,” said Steve Trossman, a spokesperson for SEIU-UHW. “The second thing is that we want them to take some of that money and put it into the clinics to better run the clinics, to make them cleaner. That really was our motivation behind it.”

Dialysis workers’ struggle

The actual procedure of dialysis is performed mostly by technicians who are notoriously overworked and underpaid.. Some technicians, paid at minimum wage, work 12 to 14 hour days. And yet DaVita and Fresenius, the two companies that own 70% to 80% of the for-profit clinics in California, have had over 15% profit margins in recent years.

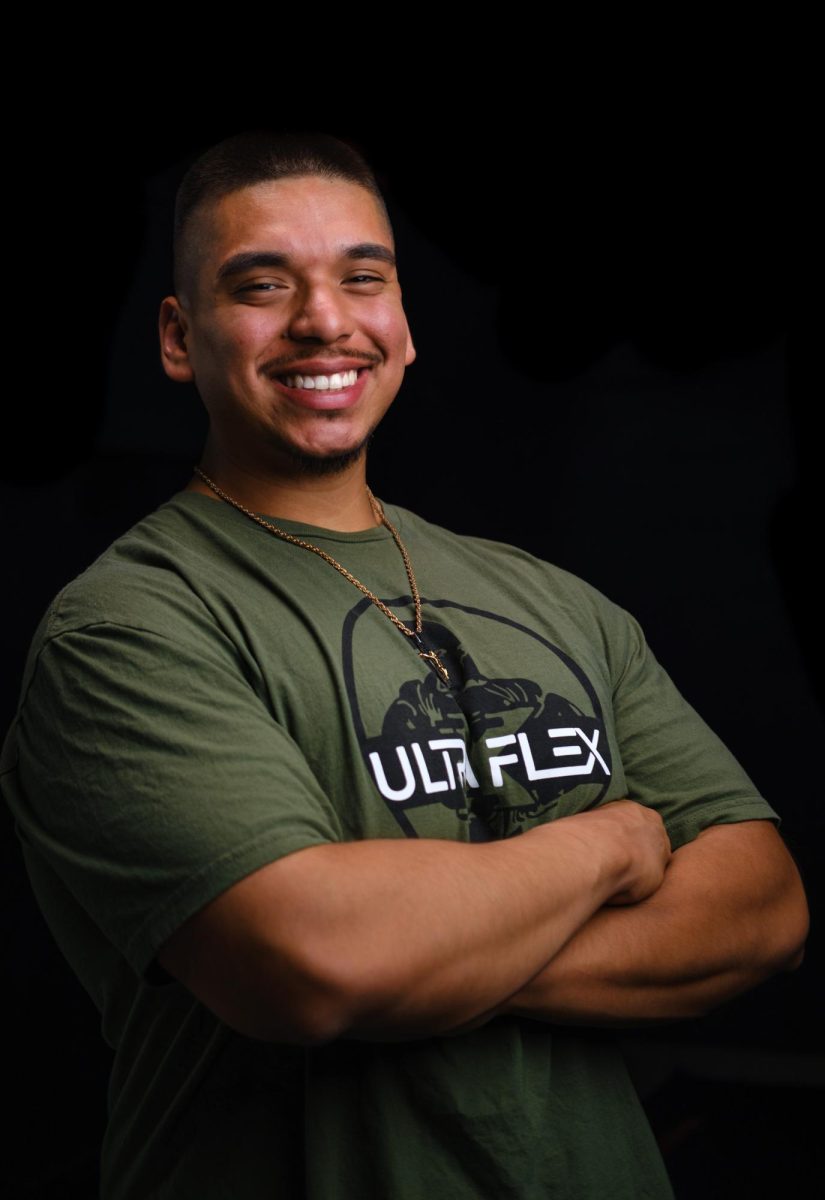

At the same time, DaVita has a history of firing union organizing employees, including Emerson Padua, an employee of the company for 16 years.

Forming a union only requires 51% of the workers of a group agreeing but that has been tough to do because the companies “have shown a willingness to fire people. It’s just really easy to intimidate people and to scare the shit out of them, quite frankly,” Trossman, the union spokesman, said.

Some technicians agree that unionizing is needed but they wonder if millions of dollars are simply being squandered by the union on fighting over a measure that may not be helpful.

For instance, Michael Morales, owner of Dialysis Education Services, a trade school for dialysis technicians, questioned the logic of the measure.

As a child, Morales helped his uncle, who performed home-dialysis, and ultimately found himself in a technician’s uniform, too. He said, “Why is SEIU-UHW focusing on this clinical issue rather than the labor issue, work environment, collective bargaining?”

The complete 2020 voter guide is available here.

Community News reporters are enrolled in JOUR 3910 – University Times. They produce stories about under-covered neighborhoods and small cities on the Eastside and South Los Angeles. Please email feedback, corrections and story tips to UTCommunityNews@gmail.com.