To this day, Yamileth Esmeralda Ramos Zavala cannot eat burritos and the smell of chicken makes her gag.

That’s because for one month and 10 days, during her 3,000-mile journey to the United States from El Salvador, she only got one meal a day: Cold burritos and dry, rubbery chicken.

I’m lucky to have any food at all, she would tell herself, often forcing morsels of food into her mouth.

Some days on the trip, she would spend the day in a dark room laying on a hard floor, or when she was lucky, on a dirty mattress that reeked of bodily fluids. The time spent on a bus or truck was often just as bad. There were whole nights when the bus wouldn’t stop, causing some passengers to urinate and sometimes even defecate in the vehicle.

During the cold, dark and lonely days spent in random rooms in Guatemala and Mexico, she would fantasize about the day she would reach the U.S. and run toward her mother, finally being able to embrace her. That thought kept her going.

Since 2012, thousands of unaccompanied minors fleeing Central American countries have crossed the Mexican border, seeking refuge and asylum in the United States. Several years ago, it was considered a humanitarian crisis and the children and teenagers were allowed to stay in the country and seek legal residency.

Ramos Zavala was desperate to leave El Salvador. She was 6 when her mom moved to the United States. Her dad died a year later, leaving her to live with her aunt, who was very ill.

Three years ago, when Ramos Zavala was 17, she made her first attempt to reunite with her mother and flee rampant gang violence.

Ramos Zavala was with a group of 56 strangers from Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador. The wheel of the bus popped not far into their journey and they were thrown into jail. Somehow, she and two other girls were put into a cell full of male gang members who were known to rape women cellmates.

She befriended a guard, convincing him to move her to a cell with women and children. She doesn’t know what happened to the two other.

Her second journey started days after the first.

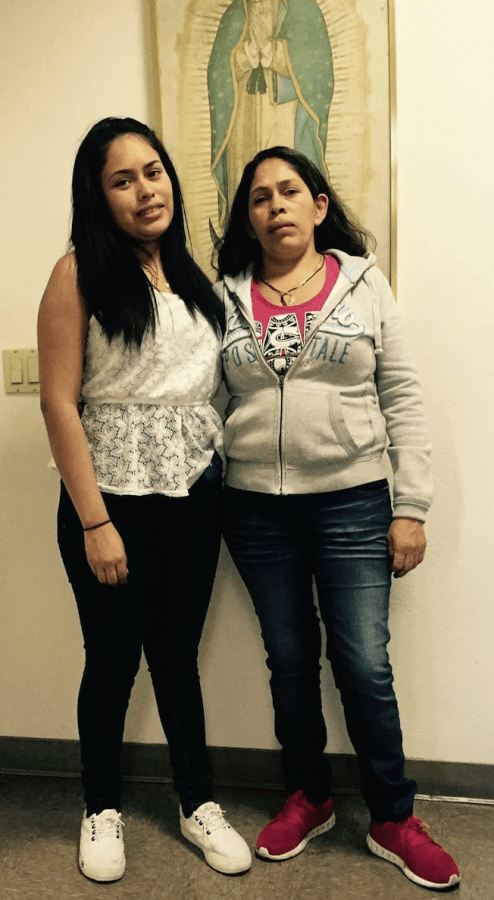

The day she finally saw her mother after 11 years of being apart, both women felt a mix of emotions. Ramos Zavala felt her mother was a complete stranger.

Her mother, Edith Patricia Zavala, was relieved after the anguish she felt knowing about the dangerous journey. She also felt joy at seeing her daughter’s face.

Her mother, Edith Patricia Zavala, was relieved after the anguish she felt knowing about the dangerous journey. She also felt joy at seeing her daughter’s face.

“During the days of her trip, I was very worried about all the dangers on the way…When I saw her I felt happiness, nostalgia, everything,” Zavala said.

But both found it tough at first to trust and connect with one another — a common issue when families are reunited after immigrating separately.

“It was very complicated. It’s difficult to explain, but we did not comprehend each other,” Zavala said.

Her daughter was advised to apply for asylum, since she had experienced vast poverty and violence. She was granted asylum in less than a year of her application. But asylum denial rates have steadily increased in recent years. The denial rate was 65 percent in fiscal year 2018, up from 42 percent just six years before, according to Syracuse University’s Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC).

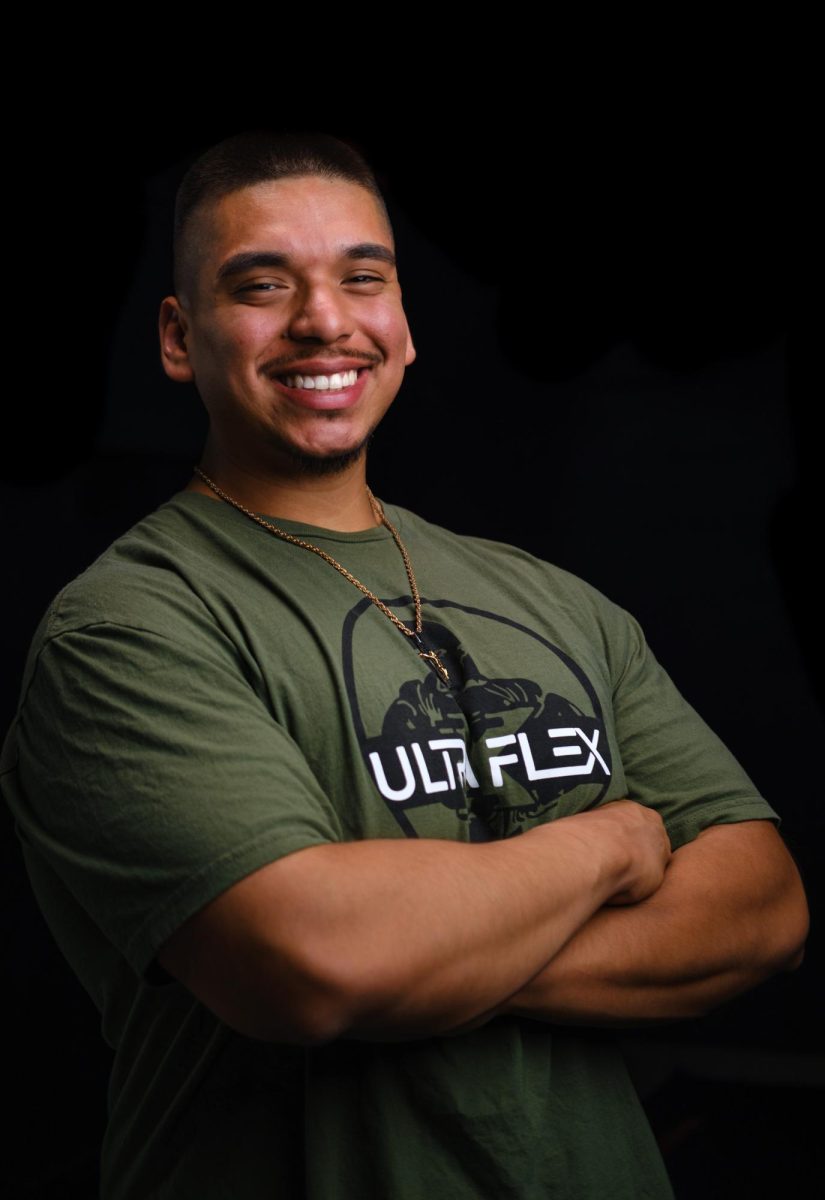

Fast-forward a few years for Ramos Zavala, she now has a green card and her relationship with her mother is much better. She works at a warehouse in South Central L.A. and is working hard to both improve her English and finish her high school credits in night school.

She said she knows how lucky she is: “I want to keep on studying… and have a career. I was not given that possibility in my home country, but I now have an opportunity in this country to make that possible for myself.”

Community News reporters are enrolled in JOUR 3910 – University Times. They produce stories about under-covered neighborhoods and small cities on the Eastside and South Los Angeles. Please email feedback, corrections and story tips to UTCommunityNews@gmail.com.