Buried dreams, generations of trauma in historically Mexican American area

Former residents of Palo Verde, La Loma, and Bishop tackle lasting impacts of displacement

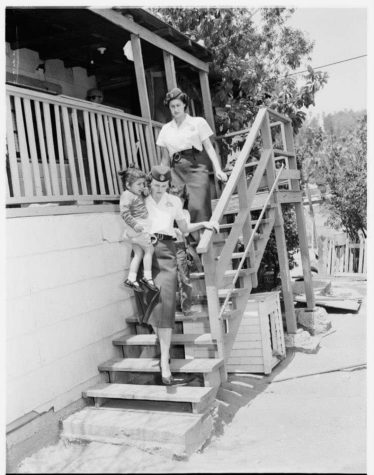

Arechiga family camping outside after their homes were destroyed. Photo courtesy of Melissa Arechiga.

To the hard-working families in the communities of Palo Verde, La Loma, and Bishop, their neighborhoods were idyllic in many ways.

Vincent Montalvo and Natasha Zarate said their grandparents described the tight-knit communities there with weekend barbecues enjoyed in yards divided by cacti and clotheslines, visited by the occasional roaming chicken or hopping rabbit, and peppered with fruit trees or gardens growing plants like parsley and bright-yellow mustard blossoms.

What’s left there now? Trauma and baseball games.

That’s according to half a dozen former residents and their family members interviewed by UT Community News.

The city of Los Angeles kicked many Mexican American residents out of their homes in these neighborhoods in the 1950s. The land was supposed to be used to build public housing but the city ultimately sold it to the owner of the Dodgers baseball team, who had the stadium built there, according to the Zinn Education Project. The project is named after Howard Zinn, whose book, A People’s History of the United States, reshaped how Americans see their own history.

“One of the most painful moments for my grandfather was when they took the roof off the Palo Verde Elementary School. People did not even have the chance to take their jackets or school supplies out,” said Montalvo, a Lincoln Heights neighborhood council executive committee member and treasurer. “The city officials went in, left the school furniture in there, they built over the walls, then they just filled the school with dirt and buried it down there.”

Los Angeles city council members and the L.A. Dodgers’ officials could not be reached despite emails and messages on social media.

Harsh memories of the evictions

In an interview this month with UT Community News, San Pedro resident Melissa Arechiga says that her mom was a 5-year-old when the last evictions happened in 1959. Her grandparents used to own their house in Palo Verde.

Her grandparents sat her mother, Jeannie, on a chair just inside the front door.

“Maybe that would make the sheriffs feel a bit of empathy,” her grandparents thought, according to Arechiga.

As she shakily held her hot chocolate and heard noises outside, her mother recalled feeling scared, Arechiga said.

The sheriffs kicked the door open.

“Wait, there’s a little girl right here,” they said, according to Arechiga.

Jeannie’s aunt was dragged out of the house and both were forced into a police car.

Little Jeannie was scared and hungry. So an officer gave her a tuna sandwich and she took a bite.

“Don’t eat their food,” her aunt snapped. The little girl immediately threw the sandwich out of the car window and down the hill, according to Arechiga.

Meanwhile, next door, Montalvo’s mother and grandparents were terrified watching the evictions unfold.

“I remember that day vividly. We were so scared,” Adela DeNava, who was 23 at the time, said in a recent interview with UT Community News. “We watched in horror as the Arechiga family was dragged out of their home and bulldozers were immediately brought in and destroyed the house.”

Her husband, John DeNava, 31 at the time, attempted to stay calm.

“I was trying to comfort my parents as they started to panic because our house was next,” he said. “At that moment, we felt like there was no way out and we had no resources to stop what was going on.”

The DeNavas, who now live in Eagle Rock, said the memories are burned in their minds forever.

“They didn’t just crush our homes, they crushed our hearts,” Adela DeNava said.

‘Stolen’ land and dreams

Montalvo said that his family owned multiple homes at the time and had a chance to build generational wealth.

“The land was basically stolen from those people because they weren’t paid a fair value for their home,” Montalvo said. “They had a chance at the American dream…But I guess the dream was never designed for people like us.”

Similarly, Boyle Heights resident Linda Solis-Perez says that her uncle Antonio Hernandez, a labor worker, used to live in Palo Verde with his family.

Solis-Perez said a lot of families didn’t have the money to fight legally when the city came in and offered settlements.

“My uncle chose to think about taking the settlement or not, but when the city officials came back again, he no longer had a choice and was forced to leave,” Solis-Perez said.

South L.A. resident Zarate says that these displacements affected her family for four generations.

“My great-grandparents and my grandparents used to live there. They owned their homes because my great-grandfather and great-uncle built the house and left it to the generations to follow,” she said. “My grandmother and all 14 of her children were uprooted from a large two-story family home to a one-bedroom apartment in the projects on the East side.”

Zarate has gone from living in an apartment to not having anywhere to stay and staying with family members.

“If my family was able to keep their land and homes, the future generations would have not had so many housing-related problems,” she said.

Arechiga says that the displacement event broke her family, and to this day, she is heartbroken and angry over it.

“My mom has mental health issues now because of this past trauma,” she said, tearing up. “We had a hard life. Our life could have been different and they robbed us of that.”

Montalvo’s grandparents are now in their 90s. They used to tell him, “Don’t buy a house because they’re gonna take it from you.”

That’s what they believed. That was what they experienced.

“They still feel the pain and they still cry about it,” he said.

Preserving the past, embracing the future

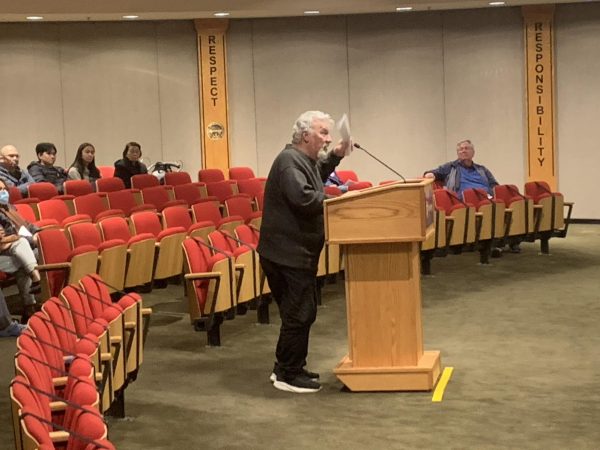

It’s a key reason why Montalvo is civically engaged and joined the Lincoln Heights neighborhood council.

“I felt that if we can identify the issue, then we can solve the issue,” he said. “We are probably some of the best people to make changes in this because we are survivors of the policies that took our homes.”

“We just have to learn to focus on possible solutions, even if they may not be something we like or want,” he said. “That’s where you learn to compromise and where you have to keep pushing to get there. That’s how I lead my life and politics.”

Montalvo is currently working on putting policies in place that protect renters’ rights, give renters supplemental income to help pay the rent, and create safe spaces for people who have inherited trauma from community displacement.

Montalvo and Arechiga are the founders of Buried Under the Blue, an organization that aims to preserve stories from the three destroyed communities buried under Dodger Stadium.

“My great-grandmother told my grandfather, my grandfather told my mother and my mother told me,” Montalvo said. “They continued to pass stories down. This is a way to pass the history down through generations.”

Arechiga said she joined the effort because she wants to embrace who she is and her family history: “I think the parts of me now that come from this experience are my strong personality and my voice. When I talk, I can hear my mom’s voice in me. I can hear my great aunt’s voice in me.”

Denis Akbari is a senior majoring in Computer Information Systems with a minor in Journalism and she works for the University Times as Digital Editor....

JoAnna • Dec 13, 2022 at 8:10 am

Work well done

With such a good narrative

It transport me to that time

How racism has play a big part

In too many bad events in history.