For many, the pandemic has been fraught with loneliness, economic hardships and fear of catching Covid-19 or passing it to a loved one.

Not so for 9-year-old August Toshima. He felt some fear in the beginning, but mainly, it has been a time of less schoolwork and more time to spend at home and with his parents.

August was at the doctor’s office in early 2020 when he first learned about the pandemic. He was feeling sick with symptoms of a cold. His dad had asked the doctor, half joking, if August had symptoms of coronavirus.

The doctor said something like, “Don’t worry. The news tends to hype up stories to put fear into people,” recalled Goro Toshima, August’s dad.

August’s parents explained the situation to him a bit more.

“It’s a thing that is happening, but there is a lot of excessive fear around it,” his dad recalled saying. “We have to wait to see what happens.”

August remembered feeling both fearful and excited about the thought of something so unusual happening, knowing that it only happens once in a lifetime. Soon after, he said he regretted thinking that because the pandemic ended up becoming so serious and lasted so long.

In the weeks after, August said he started noticing the streets were empty and he didn’t see anyone in sight. He said it was like a “zombie apocalypse.”

His father and mother, Ruth Katz, decided to keep August in the loop by educating him with kid-appropriate news articles on the pandemic and by being as honest and straightforward as possible.

“I wanted to inform him without scaring him, letting him know what we know and what we don’t know while also giving him a chance to ask questions,” said Katz.

August said he was bored on end for most of the quarantine.

He wasn’t the only child to feel this way: The average American parent experienced six daily announcements of “I’m bored,” according to a survey by Fat Brain Toys in 2020.

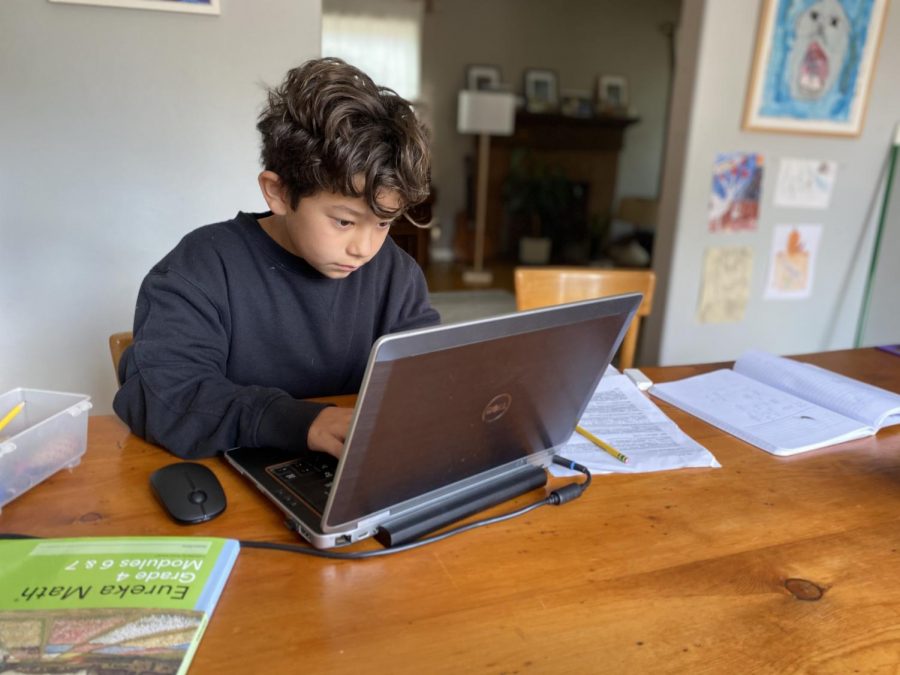

On top of boredom, there was major confusion and frustration early in the pandemic for students, parents and even teachers when it came to online learning.

August said that there were a lot of apps to login to and many confusing directions. His dad agreed.

“Even for the grown ups, it was confusing,” Goro Toshima said. “Especially in the beginning, it was multiple apps to understand and LAUSD didn’t know what they were doing and still trying to figure out an effective way of teaching.”

He’d ask other parents, “What app should we be on now and how do we log in?”

Things improved, he said, in the fall =when LAUSD started changing its ways of learning: “It was more streamlined, where you can just go to one website and do all their work on there.”

Over time, August said he got to a place where he was able to do online learning “in my sleep.” There were also some perks: He was able to sleep in and he got better grades.

August said he did miss his friends from school, remembering the memories and jokes they shared.

August said another benefit was having more time with his parents since they both worked from home during the pandemic.

“My dad taught me piano, and both my mom and dad helped me get better at school by helping me with my homework,” added August.

August passed any free time playing video games and making cardboard props. He also added something new to his daily routine: Going to the hammock swing-chair in his room to sit back and “think through things.”

He said he usually leaves the lights on and plays rock music: “Rock is calming to me.”

Swinging in his hammock with the music playing helped him let go of any stress or anxiety he felt.

He said it’s “a relaxing hour to my day,” he said.

August said he thought about four things during the hour.

First, he would think about the pandemic. For instance, he might think about how it started with “a bat getting infected and someone eating that bat, who got sick and spread it all over the world.” He sometimes pondered ideas for turning the concept of how the pandemic started and what hardships people faced into a children’s book.

Second, August would spend time thinking about what cardboard props he could make next, sometimes writing out his ideas on paper. He had already made more than 40, including weapons he saw in video games or props from the Avengers movies.

Then, August would think of video game strategies he could use the next time he played with his friends.

Finally, August would think about nothing. He said he used this time to “clear his mind” and sometimes meditate for the last 15 minutes, staring at something in his room while his mind was elsewhere.

August said he wouldn’t take notes for the most part. He would “process everything in my mind and understand them.”

Despite some of the perks he is experiencing as he continues remote learning, he said one thing he’ll never forget about this time is that “pandemics are a force to be reckoned with.”