Keely and Du in the post-Roe era

Warning: This article contains discussion of topics of sexual assault, abortion, forced birth and other sensitive issues.

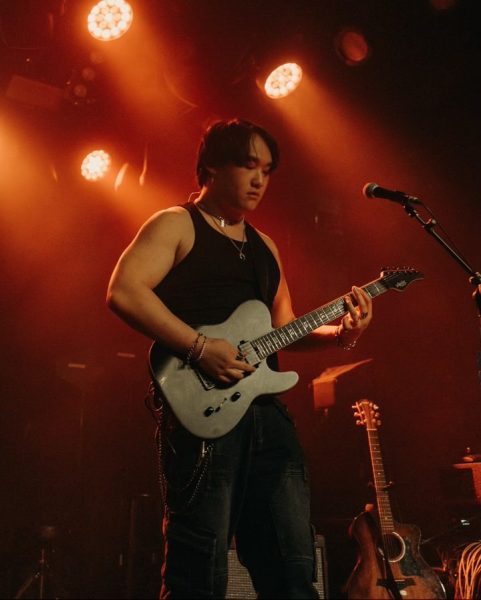

Theatre and Dance Department, Kai Marshall

Keely (Amy Luna-Beltran) is yelled at by Walter (Henry Alexander Meza) in an attempt to convince her that going through with the pregnancy is the “best option for the child.” Photos courtesy of the Theatre and Dance Depart- ment. Photo by Kai Marshall.

“Keely and Du,” a production run through early October by the department of theater and dance, centers the voices of underrepresented women in the ongoing conversation of abortion rights.

Written by an unknown playwright in 1993 under the pseudonym Jane Martin, the play tells the story of a kidnapped woman (Keely) seeking an abortion after being raped by her former spouse. Her kidnappers ascribe their reasoning to their religious views, intending to have her carry out the rest of her pregnancy. Keely soon forms a reluctant friendship with the elderly nurse (Du), who watches over her amid the traumatizing circumstances.

With a runtime of around two hours, the play features no intermission, a deliberate decision made by the play’s director, Laura Dickenson-Turner, revealed in a discussion with the audience on what an intermission would look like since the main character was supposed to remain chained to the bed.

Amy Luna-Beltran, who plays Keely, sees the lack of an intermission as an essential aspect of the play’s central theme.

“You get to experience, for however long, what it’s like to be a woman; to be subjugated, to be tied to a bed, to be forced to deal with your rapist,” Luna-Beltran said. “You’re forced to be in this woman’s experience because she doesn’t get an intermission.”

Henry Alexander Meza, who plays Walter, the religious extremist in charge of Keely’s kidnapping, described his experience playing a character with views vastly different from his own.

“It was very hard to get into [the character] because I’m not a man of faith,” Meza said. “As Henry, I start judging him because I don’t believe the same thing he believes in. But it’s the job of the actor not to judge your character. When I’m Walter, I have to believe he thinks he’s saving two lives.”

Each performance is followed by a “talk-back” in which the audience themselves have the opportunity to discuss the subject matter with the actors. The cast members asked the audience questions such as how they felt about religion versus radicalism.

Audience member and former student Migonom Delarre shared her interpretation of the contrasting ideologies.

“It’s the same side of a different coin,” Delarre said. “You can go too far in one direction or the other…and start to lose people to your cause.”

Another audience member, Dino Lalli, shared his overall reaction to the performance’s underlying themes.

“it shows all the many ways that women are oppressed and how religion has been used since its foundation to keep women in line,” Lalli said. “I think it’s an incredibly powerful piece, and unfortunately…it’s still relevant.”

The current interpretation of the play is one of the few to break away from using a white actress as the main character, according to Luna-Beltran.

“I found out that there was only one other production with a woman of color,” Luna-Beltran said. “Not just that, but I am a bigger woman. All the women that have played this role are small women. Throughout the process, it’s been an interesting discovery to see what happens when you put a woman that we see every day in real life from Boyle Heights in that situation.”

Jessica is a third year journalism major and creative writing minor who currently works as reporter for the University Times. In her spare time, Jessica...