Lost in translation: Misinterpreting ‘notario’ can lead to deportation

Maria Sanchez considers herself one of the lucky ones who managed to successfully gain citizenship.

Notary public and notario publico. They seem like the same occupation in two different languages, right?

That false assumption has led to some immigrants being deported, according to local lawyers and the American Bar Association.

Latino immigrants who want to apply for a green card must be very careful who they get help from.

Immigrants using fraudulent green card services face deportation, experts say.

“The literal translation of ‘notario publico’ is ‘notary public.’ While a notary public in the United States is authorized only to witness the signature of forms, a notary public in many Latin American (and European) countries refers to an individual who has received the equivalent of a law license and who is authorized to represent others before the government,” according to the Bar Association. “As a result of the advice or actions of such individuals an immigrant can miss opportunities to obtain legal residency, can be unnecessarily deported, or can be subject to civil and/or criminal liability for the filing of false claims.”

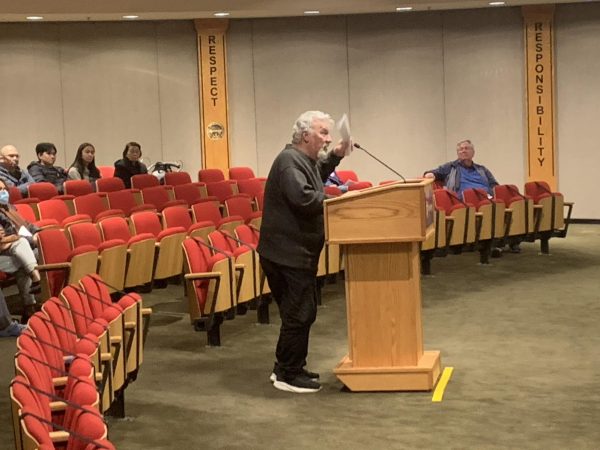

Attorney Jose Jordan, who practices in West Covina, said notario scams are a major issue in the Latino community in Los Angeles.

“My biggest problem is that I have people coming to me for help, but there is really nothing I could do for them,” Jordan said in a recent interview.

He said immigrants can apply for a green card in various ways. For instance, a family member who is a U.S. citizen can “sponsor” them or their employer may apply for them.

Jordan said the application process can take ten months to two years. However, some cases take longer than others because complications are involved.

Jordan said there is a battle brewing between attorneys and “notarios,” who are not qualified to deal with immigration services.

“They charge thousands of dollars to submit an application that eventually puts these people into deportation orders. They end up being kicked out of the country. In another sense, they basically pay this person to deport them and these shops are all over L.A.,” Jordan said.

Several notarios could not be reached despite phone calls.

Maria Sanchez was 15 when she followed her oldest brothers to the United States from Mexico in the 1980s.

She came with the hope of pursuing a better life for herself and her family. The 22 years she has worked as a housekeeper at the Pacific Palms Resort in La Puente has allowed her to single-handedly raise her three daughters and send them to school.

She said her visa and years later, U.S. citizenship, allowed her dramatic upward mobility. But she teared up recalling how much undocumented friends and family members struggled over the years.

She said people felt clueless and went looking for whatever seemed helpful to them. “No es que son mensos. Es que la majoria no tiene educacion de reconocer lo malo,” she said. “It wasn’t that they were stupid. It was that they were not educated and they didn’t know any better.”

She recalls years ago, the biggest issue was that people did not have the money that the attorneys were charging. So if help came around and it was much cheaper, they would take it.

“La gente no sabe en lo que se meten. Ellos piensan que toda la gente aqui es buena y que los van ayudar. Confian en ellos y mira adonde llegan,” she said. “People don’t know what they’re getting themselves into. They think that everyone has good intentions and that they’ll help them out. They trust them and look where that gets them.”

Community News reporters are enrolled in JOUR 3910 – University Times. They produce stories about under-covered neighborhoods and small cities on the Eastside and South Los Angeles. Please email feedback, corrections and story tips to [email protected].