Maria Ruiz feels that South Los Angeles has been “a forgotten city for so long,” in so many ways.

One way is the dearth of pharmacies.

The South Central resident treks more than a mile from home once or twice a month to get medication from the CVS pharmacy on Central Avenue.

Getting medication for her elderly parents is not easy; the long wait times and a small staff results in pick-ups taking several hours, even if the prescriptions had been filled several days prior.

“People have to travel more, into Huntington Park, into Inglewood,” Ruiz said. One friend, she said, recently had to travel as far as Carson to get what they needed.

“It’s like we’re just totally forgotten,” she added.

Many neighborhoods in South L.A. are in what’s called a pharmacy desert, an area with limited or no access to pharmacy services, and where residents experience difficulties reaching them due to a lack of transportation or time.

Staff shortages at large chains like CVS and Walgreens, and the closure of Rite Aid stores recently amid its bankruptcy filing, has made it increasingly difficult for residents to receive medications on time and make the long trips across town. These inequities disproportionately impact Latino and Black communities in the city, according to studies from USC and University of California, Irvine.

Dr. Kim Benjamin, a reading specialist at an elementary school in South L.A., said getting the necessary medicine on time — or at all — was an arduous task.

In 2020, her mother needed medication for pancreatic cancer and other issues. Due to shortages exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, vital medicine like insulin and fentanyl was scarce, and Benjamin would often have to make the trips to multiple locations around L.A. and Inglewood to get what was needed.

“You become numb to it,” Benjamin said.

When her mother later entered hospice care, only then did resources become more readily available. She said the emotional strain of going back and forth was “frustrating” and “a test of patience,” and wished there had been more care before it reached that point.

An analysis of licensee data from the Department of Consumer Affairs (DCA) and spatial mapping regions of neighborhood boundaries from the Los Angeles Times’ “Mapping L.A.” project shows about 344 active retail pharmacies within the city of Los Angeles and some unincorporated regions of the county. Pharmacies within South L.A., Central L.A., Northeast L.A., the Eastside, and the Westside were plotted using addresses and latitude-longitudinal data. Only data the DCA listed as being within the city of L.A. was used.

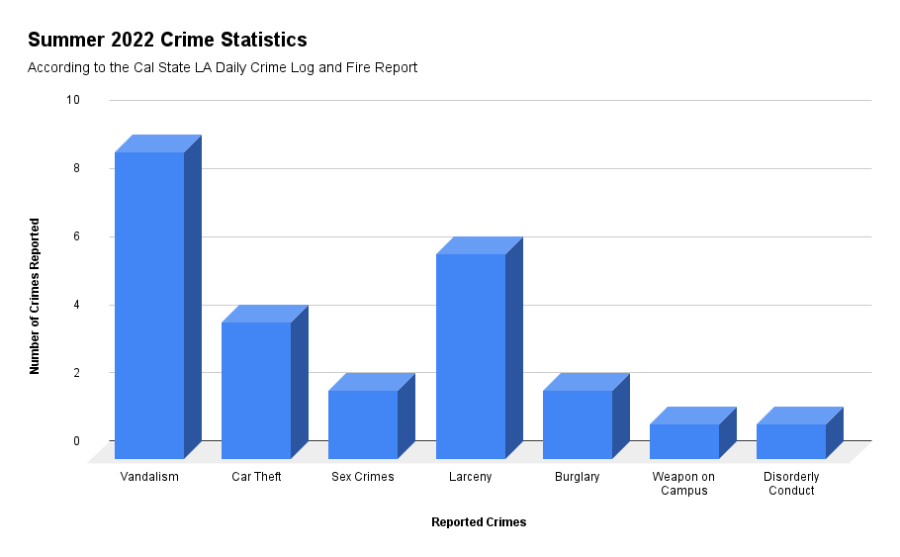

A UT Community analysis of 17 neighborhoods in the city and some unincorporated parts of Los Angeles County found:

- As a neighborhood’s average household income increased, the average number of pharmacies per 100,000 people also increased. For instance, the South L.A. neighborhood of Watts has the lowest average household income of the 17 neighborhoods, $25,161, and the lowest number of pharmacies, fewer than five per 100,000 residents. West Los Angeles in comparison, has the highest average income, $86,403, and the most pharmacies, nearly 37 per 100,000 people.

- Pharmacies in South L.A. were more spread out over larger distances than pharmacies in West L.A. or Central L.A.

- Neighborhoods in the Westside such as Sawtelle, West L.A. and Rancho Park have a greater number of pharmacies per 100,000 people compared to neighborhoods in South Los Angeles such as Vermont-Slauson, Hyde Park, and Watts.

- Koreatown and Westlake are exceptions to some of the trends found. For instance, the income levels of both neighborhoods, $30,558 and $26,757 respectively, are comparable to those in South L.A. And yet they have some of the highest number of pharmacies per 100,000 residents: 28 for Koreatown and 24 for Westlake.

Chart comparing the average household incomes of 17 neighborhoods with how many pharmacies they have per 100,000 people. Some neighborhoods don’t have more than 100,000 people but this rate allows for a more accurate comparison of the neighborhoods. Data visualization by Jackson Tammariello, using data from the Department of Consumer Affairs and the U.S. Census.

Map showing active retail pharmacies within the city of Los Angeles and some unincorporated neighborhoods of L.A. County, including Willowbrook, Florence-Firestone, and East Los Angeles. Data visualization by Jackson Tammariello, using data from the LA Times’ “Mapping LA” project and the Department of Consumer Affairs.

Hyde Park and Sawtelle have similar neighborhood sizes, 2.88 and 2.70 square miles respectively, and comparable populations, both slightly more than 38,000 people, according to 2008 Department of City Planning data. However, Hyde Park has an average household income of about $39,000 and fewer pharmacies — only 2 — which is a rate of 5.15 per 100,000 residents. Meanwhile, Sawtelle on the Westside has an average income of $57,000 and more pharmacies, 11, which works out to 28.43 pharmacies per 100,000 people.

Residents often travel to other neighborhoods where their main pharmacy is located, so a small neighborhood that is without a pharmacy specifically located within the boundary lines of a city map does not show the whole picture. The distance from one’s home is a critical factor in what makes a neighborhood a pharmacy desert.

The Pharmacy Access Initiative, a mapping tool developed by USC professor Dima Qato and her fellow researchers, uses U.S. Census data tracts to determine distances between pharmacies and where residents live, designating areas as a non desert, half-mile desert, or one-mile (or greater) desert.

Many parts of Vermont Square, Vermont-Slauson, Watts, and Hyde Park are characterized as half-mile deserts, and a sizable portion of Florence is considered a one-mile desert. Areas in East Los Angeles and the Northeast also experience half-mile and one mile deserts, while most of the Westside is labeled as a “non desert.”

Cal State LA student Marina Gomez lives on the edge of Watts and Lynwood, and has to take the bus to the pharmacy due to not owning a car. She said many seniors rely on public transportation because of the lack of walkable distances.

“There’s no actual bus that takes you to the CVS,” Gomez said. “I have to walk 10 to 15 minutes, walk back, and go back on the bus.” It’s increasingly difficult for seniors with disabilities, she added.

Jasmine Johnson lives in Hyde Park, but lived in Mid-City a few years ago. Recently, she went into a local pharmacy to pick up prescribed medications that she was told were ready. Upon arrival, she was told it would take another two weeks. At her old pharmacy in Mid-City, she said it was a different story.

“I’ve never waited for medication previously, the store was blocks away as opposed to anywhere near a mile,” she said. She added that products were more plentiful and the store shelves were better stocked, in quantity and quality.

“I’m hoping that generations to come will see … that there shouldn’t be a difference and hold the powers that be responsible,” Johnson said. “Everybody needs the same type of products, access, and choices.”