The little girl who could

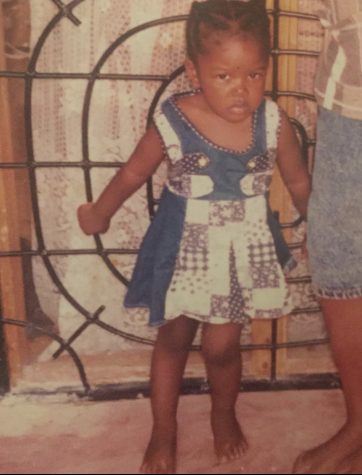

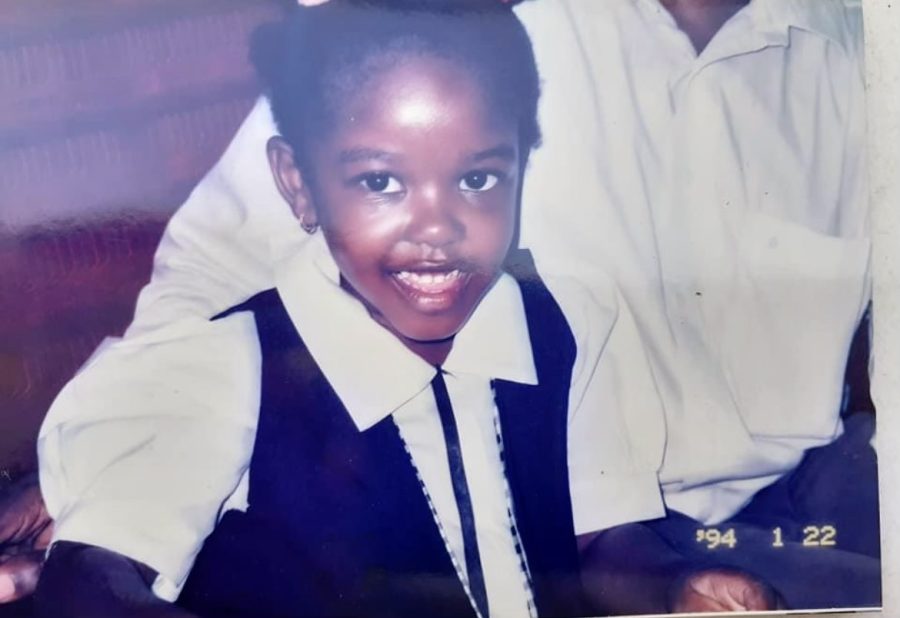

4-year-old Brenda (Photo Credits Courtesy of Louise Ndunguru)

4-year-old Brenda Mwingira. Photo courtesy of Louise Ndunguru.

As a young girl growing up in Tanzania, a developing country, the idea of attending a four-year U.S. university was almost as mythical as an old African folktale.

The fact that neither of my parents got their bachelor’s degrees made it even more likely that I’d follow suit.

My mother was a culinary chef at a hotel and my dad, whom I never got a chance to know since he had passed away when I was just 2 years old, was a local veterinarian.

My mom had to wear the hat of being a mom and dad at the same time and working two or three to support me and later, my two younger brothers.

It wasn’t the easiest upbringing but she tried. Thankfully, my grandparents were very supportive and hands-on, watching us while my mom worked.

She spent most of our childhood working overseas since there were better opportunities than in Tanzania. She lived in the United Kingdom for eight years. We’d always talk on the phone but that’s not enough time for a child to spend with their parents.

I remembered she once told me, “If you keep your grades up, I’ll take you to the best schools there are for you to have a better education.”

Because I knew we didn’t have enough, I worried. I worried she’d have to work more than she already did just to make it work — which was exactly what she did.

Despite the uncertainties of life, there was one thing I knew even as a 5-year-old: What I wanted to do later in life.

“What do you want to be when you grow up?” my grandmother asked me.

“I wanna be like the lady on TV,” I said without hesitation.

I loved watching a local news channel where an anchor, Betty Mkwasa, always delivered the news gracefully.

As I got older, I realized the odds were against me. Still, I made sure I earned great grades; asked lots of questions so I could maximize my learning; and initiated various projects related to journalism.

For instance, I founded a magazine at my school, assembling a team of students who were also creative and strong writers — and the magazine continued once we left.

I also became the first chief editor at both my middle and high schools and that really shaped me to pursue my career in journalism.

“Brenda, with that mouth of yours, you could either be a lawyer or a news reporter but we’re looking forward to seeing you on CNN,” Mr. Mkali, one of my teachers at St. Mark’s middle school in Tanzania, said.

He had no idea the fire he ignited with those encouraging words.

In Tanzania, most parents who care about a quality education must pay tuition for private schools from kindergarten to college because public schools are almost all sub-par. That means despite being a single parent, my mother took a big risk by paying tuition all those years for my brothers and me. She wouldn’t stop at anything to make sure I attended the best schools. Education was very important to her.

When I moved to the U.S., I had a difficult time transitioning. It was the first time I was away from home, away from my family, away from what I considered normal.

I lived in Baltimore with my aunt and uncle who were family, yes, but I missed home. I cried so many nights, wondering if I would make it through. My mom would pray tirelessly and remind me, “God didn’t bring you all the way out there for you not to succeed. You are smart, you are exceptional and in no time, the world will get to see that.”

When I got to college, I knew I had to fend for myself and not rely so much on my mother who still had my two younger brothers to support. So, while attending community colleges in Baltimore and California, I worked full-time as a babysitter to finance my books and other expenses.

My long days of working and sleepless nights doing homework were worth it when I finally graduated with an associate’s degree.

“You really inspired me to go back to school and finish my degree. You are so resilient and I’m so proud of all you’ve accomplished despite the chaos that came with it,” my best friend Reese Richardson said when she accompanied me for my graduation photos.

The next step was a four-year university. When I got the email offering me admission to California State University, Los Angeles, I screamed and called my mom. We cried together and she said, “Daddy would have been so proud of you.”

I cried some more because the little girl in me had always wanted to make him proud.

I’m working on obtaining a bachelor’s degree in journalism and hope to someday motivate and inspire young black girls, especially from my country, Tanzania.

I sometimes compare myself to the train in the “Little Engine That Could.” Despite the obstacles that seem to be around every corner, I feel that if I set my mind to it, I’ll someday make it as a successful newscaster, delivering information to the people and providing a platform to elevate their voices.

I’m grateful for my family that motivates me and reminds me of how far I’ve come and every now and then paints a picture of what is yet to come. One of them being my Uncle Chris, the only male, and fatherly figure I know of. “You’re really going to make us all proud, now I’m telling you this because one day when you come to realize what we say and do what we tell you to do, don’t forget to say that my family told me that,” he said.

There is a Tanzanian saying in Swahili: Kila ndege huruka na mbawa zake. Every bird flies with its own wings.

With wings once supported by the wind of my mother and family and now strong on their own, I feel even the sky isn’t the limit. I’ll reach for the stars.

Flavia Ndunguru • Dec 18, 2022 at 1:05 pm

Wow baby girl you broke my tear boxes i can see the little girl with her wings we give praise to our mighty God he is who holds your hands and provides all you need.. he is watching you your faith in him lifting you up his promises are real he will never forsake you.. you are such a strong “dada” who inspires many. Keep it up dear God is with you.love mum.