Regulations legalizing street vending pose challenges for vendors

A state law intended to decriminalize street vending has led to an abundance of food options in certain areas such as Valley Boulevard in El Monte. Some of the loyal customers who wait in lines — for foods like a classic street taco to Tajin-sprinkled fresh fruit and elote — say it feels good to buy hand-prepared food by people who live in their city.

However, Community News interviews with some vendors and a local businessman show that many are having serious challenges operating legally because of complex and costly requirements imposed by local jurisdictions for vending permits.

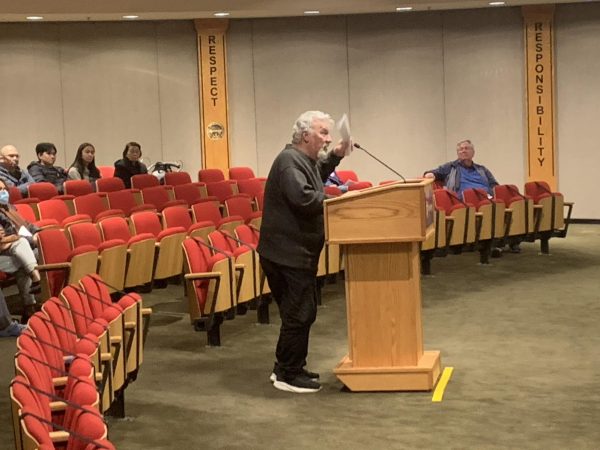

There’s a perception that it is now “easier for street vendors to operate. But there’s a huge misconception of what ‘easier’ actually means,” Jesus Covarrubias, who created Integral Business Services, LLC, this year to help vendors understand all of the new requirements that must be met in order to comply with the law.

The Safe Sidewalk Vending Act, which went into effect in Jan. 2019, prohibited local authorities from “regulating sidewalk vendors, except in accordance with the provisions of the bill.”

This meant that many cities had to create permit systems for sidewalk vendors and allow them to sell their wares.

In El Monte, for instance, the Mobile Vendor Cooking requirements include a long list of rules that must be met by street vendors who are cooking and selling food on the streets.

Of these rules and requirements, the most important ones are often the most difficult to obtain, such as a stationary vending permit and the certificate from the L.A. County Department of Health, according to Covarrubias.

In an interview, Covarrubias noted discrepancies between the city and the county requirements. For instance, El Monte technically allows stationary vending permits but they must get approval from the county’s Department of Health.

“If you talk to the L.A. County, at least for the last two [or three] weeks that I’ve been talking to them…there hasn’t been any proof that says that they actually give out these licenses. In fact, when I speak to them, they say, ‘Oh yeah, we don’t give stationary permits to any vendor who’s just out there; It has to be a mobile unit,” Covarrubias said, adding that the regulations for mobile vending are much stricter, so it makes it virtually impossible for people who want cheaper stationary vending. “So they both send you to each other, but none of them agree with each other.”

A representative of the Finance Department of the city of El Monte, and its Business License area, said in an email that the city allows for stationary vending permits and that many of the requirements that make it difficult to finalize the process and get all of the permits come directly from L.A. County’s Department of Health.

“It is true that costs to be a sidewalk vendor can be high. However…the city’s permit fees remain low,” the representative said, adding that in El Monte, the permit fee for sidewalk vendors is $158 and another $100 per location. There is also a $29 processing fee. The city has not yet specified whether the fees are one-time or recurring.

A fee schedule noting various fees, each amounting to hundreds of dollars, is part of the Mobile Food Facility Plan Check on the Department of Health’s website, however, it’s unclear whether vendors are required to pay these fees in combination with the city fees.

This issue has affected many of the new street vendors in El Monte, as it is difficult for them to get a clear and cohesive guide of all the equipment and certifications they need. This has resulted in many vendors buying expensive equipment such as their carts for their products, only to be later told that the equipment that they have would keep them from getting a permit.

Hector Aguilar began street vending as a way to make ends meet when he lost his job during the pandemic.

He said in an interview that he had no idea how difficult it would be to get vending permits.

Aguilar, who owns and operates Phizh, said that he searched for requirements online and left voicemails to the contacts he found.

“I called for like two, three weeks daily, leaving voicemails and I got no response. So to the best of knowledge, I went out and bought equipment that I thought would be allowed to sell,” he said. “There’s information on the website but there’s not a full description of what you need.”

About a month later, the county finally got back to him. He balked when he realized “the grill they’re looking for is something that’s covered…you know $50,000 grills.”

“At that point, I was already too far in,” he said, adding that there was no way for him to replace all of the equipment that he had just purchased — and especially to do so with equipment that is much more expensive.

His fears related to his new business were almost realized on Oct. 10, when health department two officials came up to him.

“Do you have a permit?” an official asked.

“No,” Aguilar said, wondering what they were going to do next. “I’m trying to get one, but it’s nearly impossible.”

“No, it’s not. Get a permit,” one of them said, walking away.

Later, he asked some of the other vendors on Valley Boulevard what happened to them.

He said he found out that “people down the street weren’t so lucky. [County officials] threw out all their meat. They threw out all their produce, everything, you know?”

“It’s tragic,” Aguilar said. “This is people’s well-being, you know? This is their job. This isn’t like a side-gig for a lot of people.”

He said for them to take such a big loss in one day “is like going to work and losing money.”

For now, Aguilar continues to vend in an effort to support his family and to save up to someday be able to afford the correct equipment. He said that each day that he comes closer to his goal, he is thankful for his customers and for the ability to serve people in his community with freshly prepared food.

“Most of our customers are the El Monte demographic: You know, older Hispanic families…that’s who primarily shops with us…People getting off the bus, the people that are getting off work,” Aguilar said.

Vendors in El Monte aren’t the only ones struggling with county regulations. For instance, Jorge Urrea, who owns and operates the “Pushin Fruits LA” cart all around the Los Angeles area, said he had no idea the costs of meeting county health department requirements.

“When I first bought the cart, I really thought that it was just about buying the cart and buying the supplies and starting to sell. I didn’t know about the permits or licenses or anything,” Urrea said in an interview, adding that he thought his purchase of the cart came with the required permits. “I was under the impression that I can sell: I can pretty much leave that establishment where I bought my cart, go stock my cart and just sell anywhere in L.A. County, because I bought my cart there. But that wasn’t the case.”

Urrea tried to address a county requirement that vendors store their carts at approved storage facilities instead of their homes.

He went to an approved facility but a down-payment on the spot would cost $780, along with a monthly fee of $280.

He said this was more than he could afford and would defeat the purpose of him working as a street vendor: To make ends meet. Even more frustrating and stressful is that he had just spent all of his savings on a $6,500 cart and products to fill it.

“Business is hard and sometimes. I can only do it on the weekends because I have a regular job…so I’ve just been popping up everywhere without a permit…crossing my fingers,” he said.

Officials from the L.A. County Department of Health did not comment directly, but provided links to pages on its website that include information about the Mobile Food Vending Investigation and Compliance Program, as well as a factsheet with a condensed list of the permit requirements.

“Illegal vending is a serious public health hazard,” according to the page. “The Mobile Food Vending Investigation and Compliance Program is made up of ten inspectors who investigate complaints from the public. Due to limited resources, the size of the county, and the number of complaints received each day, it may take some time to address each complaint, but every single complaint will be investigated.”

Community News produces stories about under-covered neighborhoods and small cities on the Eastside and South Los Angeles. Please email feedback, corrections and story tips to [email protected].

She is a fourth-year Journalism student at Cal State LA. She is a Reporter and a Social Media Editor at the University Times. She has an interest in Music...

Julie Patel Liss • Dec 11, 2020 at 2:36 pm

Thanks for your comments. And thanks sharing your story with our student journalists, Mr. Covarrubias and Ms. Aguilar.

Jesus Covarrubias • Dec 1, 2020 at 9:43 am

We hope one day that our city can be an example for change and opportunity. Thank you for giving us a voice and letting us be a part of this.

Ruby Godinez • Nov 30, 2020 at 10:22 pm

Why do you people have to make things so difficult for good people who want to earn a living and make other people happy. Sell them the DAMM licence.

Mayra Brenes Aguilar • Nov 30, 2020 at 5:50 pm

I bought a fruit cart . cost me 4500 plus permits. Then I have to paid license for the city, another 250. Plus a parking for my fruit cart. Honestly the government is not trying to help small street vendor. They want vendors to paid a huge amount to park a small cart fruit, when this cart can be perfectly park in the house..

Rich • Nov 30, 2020 at 4:28 pm

I ate food from an unlicensed food vendor once and ended up getting sick.

Frankie Ramirez • Nov 30, 2020 at 12:17 am

I’m going to sue the city of el monte ! The food sometime’s is spoiled. As for the fruit carts it’s just the same. These people are living off the land without paying taxes. Same goes for getting recyclable’s out of the container’s in the street. There’s now law enforcement in El Monte.city officials sell the permit just to collect money. Corruption in city hall.