Growing up Black in Lynchburg, Virginia

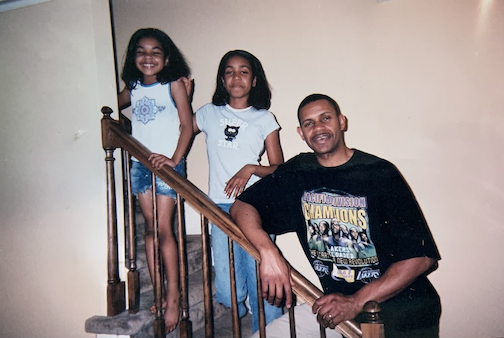

Myself, Sister and father on staircase in home

When I was 4, my parents, sister and I left West Covina, California, for Virginia, 2,234 miles away.

We ended up moving to the city of Lynchburg — a name that seemed to figuratively foreshadow our experience there.

The move was influenced by a job opportunity with my dad’s cousin and the hope for a better life for us. Safer neighborhoods and a better education appealed to my mother.

We lived in Virginia until I was 17, moving back to California the summer before my senior year of high school.

That means nearly 13 years of my life were spent in Virginia.

According to my mother, I was miserable for the first year there because I didn’t want to move.

An enchanted life – sort of

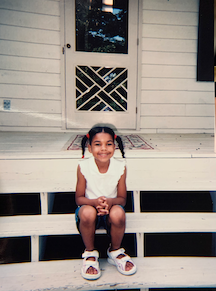

It was 2004 when we moved into our house. It was a beautiful cape-cod-style home with a large front porch. In front of the porch were beautiful flower bushes that would bloom in the spring. The house had white wood siding and dark green window shutters. There were three stories, three bedrooms and two and half bathrooms.

It had a pool with a wrap-around patio and a literal white picket fence.

Before the Obamas, it was our little Black family in a beautiful white house.

The house also had a large front yard and backyard, practically a forest, filled with trees and ready for adventure.

My sister and I each finally had our own rooms with plenty of space to ourselves. And we had a basement that was the location of many birthday sleepovers.

I am grateful for the home I grew up in, as I know how rare it is for minoritized groups to own their own homes, especially in California, with gentrification and high prices.

My dad tried to keep my sister and me in touch with our history by showing us the original “Roots” film and enriching us with Black culture – mainly entertainment like Black musicians and athletes.

He also always said I was so good at English and history because I am a Hall and I come from a long line of educators. Many of whom are my great aunts. At home, my Blackness and lineage was something to be proud of.

I’m thankful for that because the message from society was the opposite, and the “culture shock” didn’t wear off.

Take the Confederate flag, displayed flying on many trucks.

“No-Bama” was a favorite phrase during the 2008 election year. And of course, the sarcastic, “Thanks, Obama” after he was in office.

Kids would come to school in hunting camouflage gear. One time, the hallway smelled like deer pee because a kid went hunting before school.

That said, the people of Lynchburg Virginia were, for the most part, very polite and religious. They seemed to accept non-whites in a “Godly” way. As in, “We are all God’s children,” and in order to be good with God, they would accept or tolerate Black people.

I am not saying they were all like this, of course. However, as a minoritized person you can tell when you are a token or if someone is uncomfortable with you based on the color of your skin.

My ‘best’ friend

The first experiences I had with racism were in kindergarten and involved my best friend.

My family and I were at a restaurant and noticed my friend was there, too, with her grandparents.

“Alyssah! It’s Alyssah!” she exclaimed excitedly, running over to sit with us.

My mother recalled thinking this was so cute and smiled over at the grandparents, who did not share the same feelings.

“Get back over here,” her grandparents told her, giving us a mean look as if it was a disgrace to be near us.

I remained best friends with her until one day, I heard about a sleepover she was having.“Why didn’t I get invited?” I asked.

“My mom doesn’t let little Black girls in her house,” she explained.

Hurt and confused, I went home and told my parents about it.

That is when they had to teach me about racism. My mother was upset and sorry that I had to experience it. She had said not all white people are racist and could tell my friend loved me but unfortunately, her family’s racism ended our friendship.

The n-word

Another unforgettable incident was my sophomore year. I was speed walking to my math class and ran into a male friend, someone whom I always made sarcastic remarks and jokes with.

I remember teasing him that my legs are longer so I can get to class faster.

“N–, shut up,” he said, looking right at me.

He kept walking to class, and I stopped dead in my tracks, stunned.

I was in shock, I didn’t know what I had done to provoke such a nasty reaction. It was so random and uncalled for.

I wanted to tell our teacher, a very warm and kind Black woman who would have stood up for me. Ironically, I was too embarrassed to tell her – even though I was the victim of hate speech

I went home that day and told my parents and began to cry. My mother and father wanted to tell the principal and I had said it was pointless so they respectfully backed down.

The next day, that friend wanted to be all buddy-buddy with me and was nudging me and trying to talk to me.

I ignored him from that day on. I never once spoke to him again.

A year later, a mutual friend told me he posted on Facebook that the N-word just means lazy.

This is obviously false: The word is historically rooted in slavery and Black oppression.

“If it had meant lazy then why would he call me lazy for being faster than him?” I recalled thinking.

Cringeworthy moments

Another friend and her family made me feel so weird, like I was their token Black friend.

We wore these cliche race-based salt and pepper shaker t-shirts, I was the “peppa’ ”, of course. She had diy-ed them, a shirt concept she got from Pinterest.

To be sure, I really loved this person at that time.

She was one of my best friends and my race seemed to come up more with her family than with her.

I remember her telling me her father said, “We are the cookie,” a Seinfeld reference about a black and white cookie being a metaphor for solving racism.

Her family had a kind of subtle racism and “cringe” to them. When I was surrounded by all of her extended family, I was never so aware of my Blackness as I was at that moment. It could have been in my head but I felt like the literal Black sheep and as if I didn’t belong.

Once her mother told me that a Black woman accused her at a community pool of being racist.

“My daughter’s best friend is Black,” she retorted as a reason why she was incapable of being racist.

I just nodded, feeling awkward and wondering, “Why is it necessary to share that story with me?”

They weren’t mean; It was just an unexplainable energy of discomfort that I felt.

I only know because I had many other white friends whose houses I would sleep over and I never thought about my race once. It seemed more welcoming or sometimes, their parents were just not as present.

Even though I was raised to be Black and proud, my experience in a predominantly white environment negatively impacted my Black identity and self-concept – or at least hindered it from flourishing for 12 years.

It wasn’t until I was 16 and started to develop my own consciousness, and saw Blackness “trending” on Tumblr, that I decided to wear my hair curly to school. I was so inspired by Black beauty and Black movements that I started to recognize my own whitewashing.

I remember a friend once asking me to wear my hair curly to school and I had said maybe one day, knowing I would never do that – or so I thought.

My mother never permed my hair but she always pressed it with a hot comb. I would sit by the stove around 6 a.m. (two hours before school started) before picture day or the first day of school with my mother behind me with a hot comb and towel in hand. I would squeal and squirm from the heat so close to my scalp but it was always worth it when it was all done.

I had long dark hair that went down my back. Even though it was long, I would compare it to my white counterparts’ and wish my hair was longer.

I didn’t realize that I was trying to assimilate. I think the most annoying comment I would get about my hair even when straight was that it was “fluffy” and “poofy” and my friends would want to touch it. My hair is thick and naturally coily, so it would “poof” up trying to revert to its natural state. It was due to the humid weather and excessive amount of precipitation in Virginia.

Cheerleading while Black

I was normally the only Black kid in my class, or one of two or three. There were even fewer Black kids in extracurricular activities, which felt really isolating.

In middle school, I decided to go out for cheer. I remember when I joined cheerleading in 6th grade, I felt so aware of my differences.

At one point at cheer practice, I was in the bathroom crying because I overheard two of the girls saying I wasn’t good, instead of offering to help me out.

I felt like an outcast. It’s funny because if I was on an all-Black cheer team then I would just think they thought I was bad because I took longer to learn the moves. But something so simple as skin color can turn a comment into something prejudiced.

The team was definitely cliquey and segregated though. I didn’t let the negative energy stop me. I loved the cheer uniform and cheerleading and I kept cheering until 11th grade.

By that point, I was immune to the subtle race-related remarks. I did make a few friends in cheer and I remember one actually offered to help me and some other girls practice moves for tryouts.

Colorism

It was really kind of her and we were friends for a few years after that. But even with her, one incident in 9th or 10th grade rubbed me the wrong way.

She told me that she brought me up to her stepmom in conversation and she said her “cheer friend, the Black one.”

There was another Black girl on cheer who was really popular and she had a darker skin complexion than me.

“The one with the nice skin color?” the stepmom apparently responded.

My friend shared that with me, thinking it was a compliment. As if I wasn’t “too dark” or “too light” and just right, she had alluded. It was gross. I was confused as to why my skin was perceived as “nicer.”

That was the first time I had experienced colorism to my face.

My skin complexion is considered light in the Black community, but being preferred for it has never been something that made me feel good.

I have family members that come in all shades of melanin and I have always seen this as a beautiful thing; That’s how I was raised.

I understood my light-skin privilege a little bit at that point in life but never had been called out for it before then.

I can only imagine how my Black experience in Virginia would have changed if I was darker-skinned, which is an unfortunate realization.

Leaving Virginia, embracing Blackness

A lot of times, I felt stunned, sad and had no words when facing racism in Virginia.

Toward the end of my time there, my junior year of high school, I started to care a lot less about the people of the place I grew up in. I started to feel more confident in my Blackness and didn’t care if it made white people uncomfortable. I didn’t care if my natural hair was called a “bush.”

I didn’t care if people stared at me.

I even chose to do a book report on the Malcolm X autobiography in my history class just to piss off my very conservative teacher.

I felt that I was starting to find myself. It was scary at first but it became liberating. I was confident, outgoing, loud and always laughing.

I learned I could wear my hair straight one day and in braids or curls the next because Black hair is versatile. I recognized straight hair didn’t have to mean I was subconsciously trying to fit in anymore.

That is when I started my journey of unapologetic Black pride and I am grateful for my experience in Virginia. It made me stronger and wiser. It wasn’t all terrible. I had Black cousins who I could relate with and I created some lifelong friends.

My time in Lynchburg was a little traumatic but it built character and only made me proud to be a Black woman today.

It inspired my passion for diversity – not only Black inclusion but for other marginalized communities.

I know what it feels like not to feel included or to feel judged based on my skin color. It’s unfair and never OK. That understanding and empathy will inform my work in journalism and, hopefully, make me a better reporter.

Community News produces stories about under-covered neighborhoods and small cities on the Eastside and South Los Angeles. Please email feedback, corrections and story tips to [email protected].

Alyssah Hall is a fourth-year journalism major and the Senior Multimedia Reporter for the University Times. She is passionate about spotlighting minority...

Sharmila B • Aug 7, 2024 at 7:40 am

Thank you for writing this. This is how I felt growing up in rural England. Leek, Staffordshire, near Stoke-On-Trent. My experiences were exactly the same.

Jon DeWitt • May 28, 2024 at 2:39 pm

Thank you for this article. Thank you for explaining your life experience so well.

Deborah Foster • Dec 22, 2023 at 1:34 am

Awesome Memoirs

J.chelle • Aug 1, 2023 at 9:50 pm

I really enjoyed reading this! I was looking up a google search about racism in Lynchburg and this was recommended. You captivated me by the first sentence! I pray much success on your journey!

Jon DeWItt • May 28, 2024 at 2:32 pm

That is exactly how I found it.

Ida • May 4, 2023 at 9:13 pm

Hi Allysa ❤️ I Thank you for sharing your story or shall I say “ Life experiences “ beautifully said . I begin reading and couldn’t put my phone down until I read the entire story Your story was inspiring motivating as yes captivating As I think it should be as a reporter or story writer You are an Amazing writer as well as , An Amazing person❤️❤️ Continue to do exploits and Making a change/ difference in this “ONLY GOD CAN” change a man’s heart type world. I’m so glad YOU TOOK POSITIVITY FROM THIS and not POOR LITTLE OLD ME ! BUt the experience seem to have worked in your favor and Pushed you into your destiny ☝☝ BE ENCOURAGED!! And again THANKS❤️❤️❤️

Cheryl Scott • Mar 28, 2023 at 4:51 pm

Thank you for your transparency. There were no lies told in this article. For some reason, I was blinded to it as a young child. I grew up here in Lynchburg, moved away when I got married, and stayed away for about 12 years, but when I moved back, my eyes were opened, and I realized that blatant racism was there all the time. It was just like you said, “If I want to be in good with God, I have to do this.” I also find it’s a softer blow toward children. I’m glad your parents moved you away before adulthood. Blessings to you, dear.