Like many students on the Cal State LA campus, Claudia Rueda, 23, was an activist, working to help raise awareness about political issues and immigrants’ rights.

But last year, the tables turned and she had to start advocating for herself and her family after they were detained by immigration officials.

“I had been helping other people through deportation proceedings and helping families. I would see their pain but I had never [completely] felt it until they took my mom because she means the world to me,” Rueda said.

Rueda’s mother was arrested by U.S. border patrol agents on immigration charges at their home in Boyle Heights in 2017. She was released but about a month later, Rueda’s world was turned upside down — again.

It was a bright morning in May and Rueda was still in her pajamas. She went outside to move her car for street cleaning when she saw the flash of police lights.

Everything is going to be OK, she thought now that her mom was safe at home.

Her heart dropped as she saw three unmarked cars approach and corner her.

We haven’t done anything, she thought. But she was scared for her life.

Not knowing what to do, she put her hands up.

The agents asked for her ID.

“I don’t have it,” she said. “That’s her,” one of them said and another handcuffed her.

She was alarmed. What are they doing to me? Why aren’t they reading me my Miranda rights? Is this a kidnapping?

Questions buzzed through her head as they took her first to a border patrol station and then a detention center in San Diego.

The hurt, confusion and anger she felt when her mom was detained came flooding back.

What could they possibly want? They have already taken so much from us and ruined my mom’s good name. She wondered if they targeted her for protesting her mother’s arrest.

California is one of the top five states with the most people in U.S. immigration detention centers per day — costing taxpayers approximately $144 per person per day, according to FreedomForImmigrants.org, a nonprofit group that advocates to end immigration detention.

Stepping into the detention center, fear rushed through her veins.

She felt like a criminal. Human trash. Invisible.

All around her, she could see people crying. Some looked down, appearing broken. Others had fear in their eyes.

“Being inside strips you of your humanity. They make you wear old clothes and feed you food with no taste. Everything reminds you that you are not worth anything,” she said. “You’re constantly afraid to break the rules because three strikes mean solitary confinement. It’s simple things….You’re just in fear.”

“We leave the trauma in our homeland seeking asylum in the U.S. only to be subjected to another type of trauma,” she added. “It’s sad people are caged just because of their immigration status.”

After three weeks in detention, Rueda was released. She thought being back in her family’s arms was all she wanted. But something was off.

“When I got out everything felt weird, even making my own decisions and not having to ask permission to do regular things. When I’m in class I find it hard to concentrate I feel like my brain blocks everything out as a coping mechanism,” she said. “While I was in there, I developed a post-traumatic stress disorder. Sometimes I just get flashbacks and start crying and just mentally check out. I have nightmares and my depression and anxiety have worsened.”

She recalls walking with her friend one day. The friend asked why she kept looking back. She realized she was doing it unconsciously.

“I felt like someone was always watching me or following me,” she said.

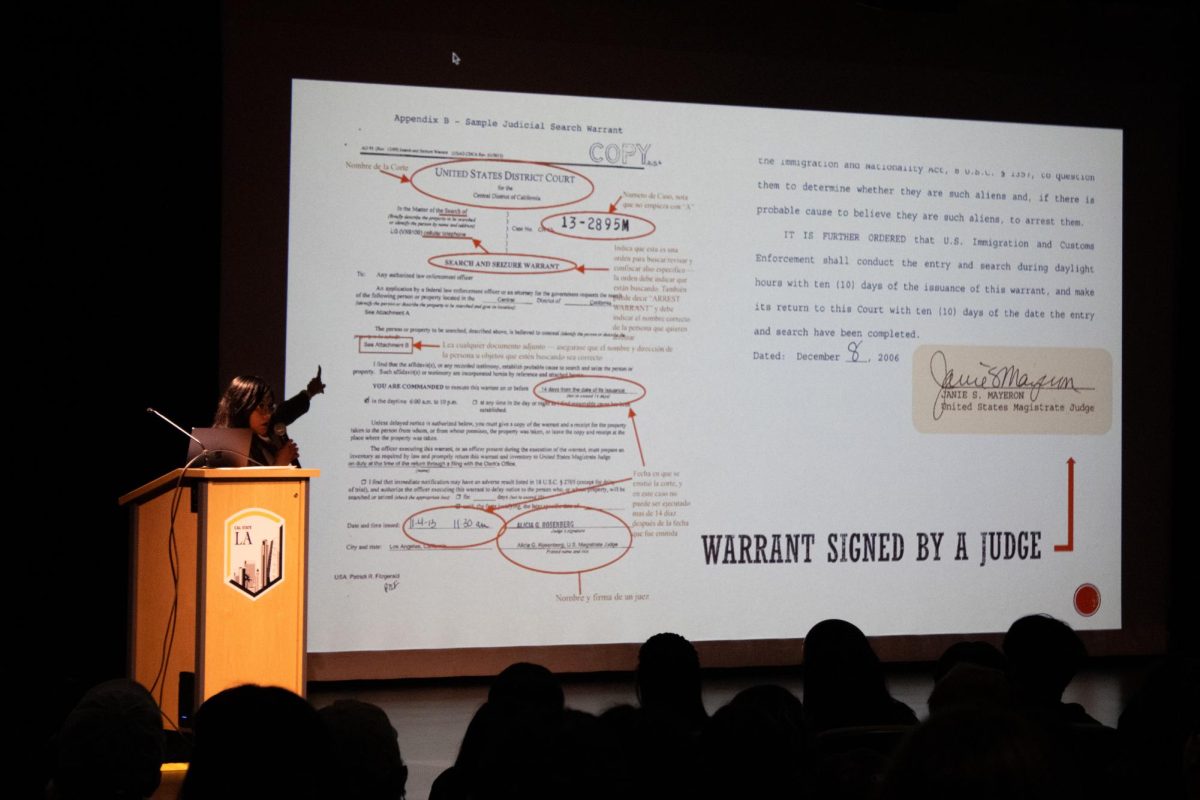

Still, Rueda isn’t letting fear run her life. She filed a lawsuit in late October against the U.S. Department of Homeland Security and others for an “unlawful and retaliatory seizure, search, and arrest” and for rejecting her Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) application. She has even faced her anxiety about speaking in public, holding a press conference about the suit. The Department could not be reached for comment despite calls and an email, but some supporters of immigration enforcement say the rules about who should be allowed to enter into the country should apply to all people.

“This lawsuit is no longer just about me. Being public and fighting is a way to tell my story and inspire others,” she said.

Family, friends and even classmates showed up at the event to support Rueda, standing firmly behind her as her voice was heard through the streets of Los Angeles.

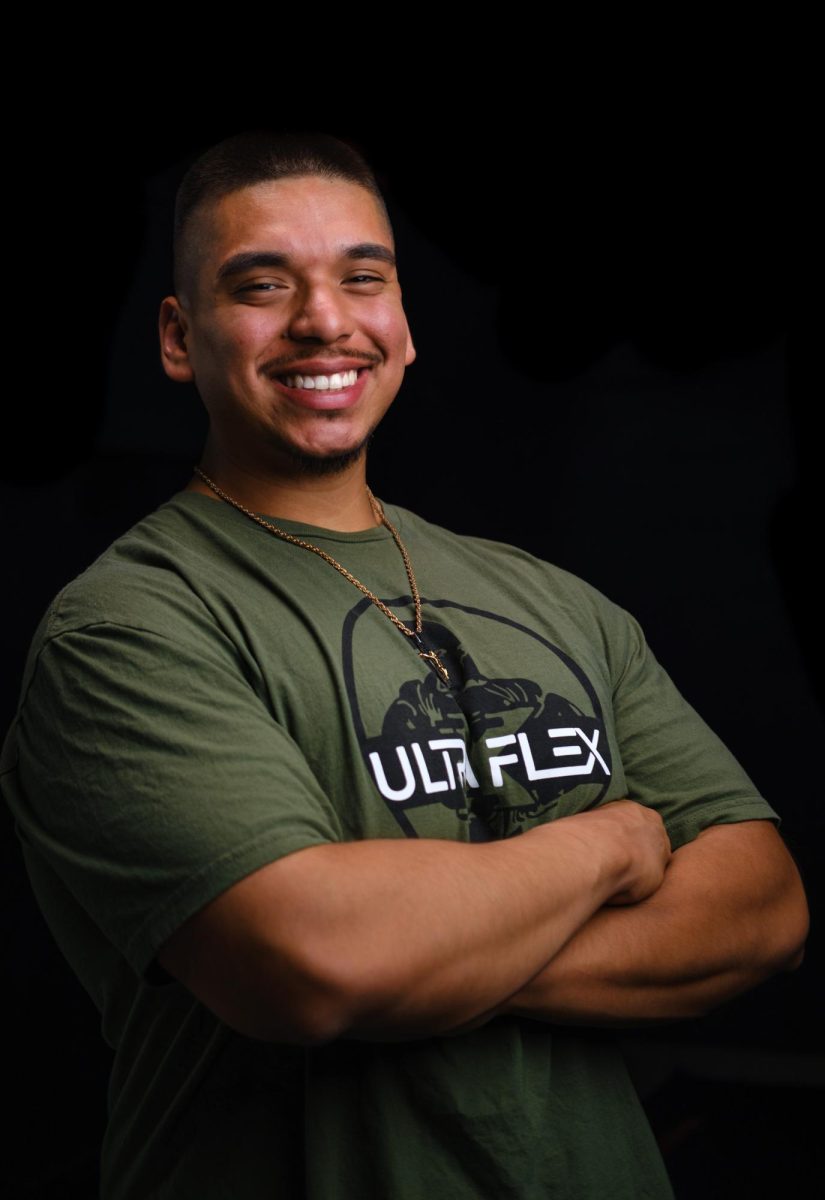

Octavio Renteria, a classmate who attended, was moved by Rueda’s story.

“It was shocking to see that everything we are learning about, pertaining to immigrant experiences in class, she is actually experiencing. I have admiration for her, and I see her as strong. If she needs help with anything, I’m on board,” he said.

After the event, Rueda was still jittery as she heard chants. To her surprise, people were saying her name.

At that moment, she knew she was not alone: “People care about and support me. I’m gonna do this and tell the world what’s going on. I just told my truth and nothing is scary about that.”

Community News reporters are enrolled in JOUR 3910 – University Times. They produce stories about under-covered neighborhoods and small cities on the Eastside and South Los Angeles. Please email feedback, corrections and story tips to UTCommunityNews@gmail.com.

Je • Apr 18, 2022 at 3:59 pm

Epic