Art and healing during a pandemic

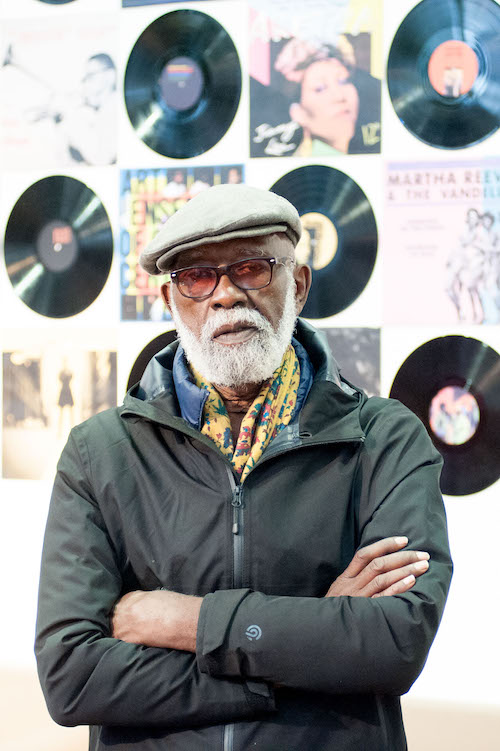

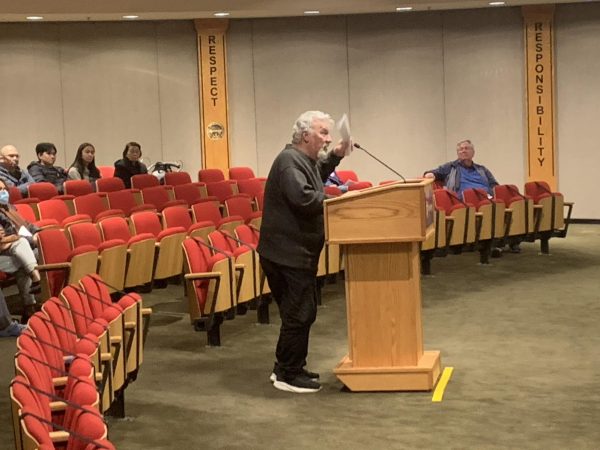

If Leimert Park is considered an artistic and cultural hub, at least part of the credit goes to Ben Caldwell, who started the Leimert Park Art Walk 10 years ago and has worked on various projects in the community for decades.

People didn’t always appreciate the artistic ventures and there were other obstacles along the way.

Some people complained about the “noise” from drumming circles. When Caldwell started KAOS Network – a media production facility that works with universities on projects – it took time to build its reputation.

Then, there were moments of distrust between the community and the police, especially after the brutal beating of Rodney King in 1991 and the acquittal of police officers in 1992, sparking riots.

Around that time, Caldwell worked with an artistic youth group called Project Blowed.

Project Blowed, a formidable force of underground hip-hop, held open mic nights, where up-and-coming DJs, break dancers, and masters of ceremonies, put on displays of artistic prowess.

During one of these events, he recalled watching an M.C. by the name of Medusa in the thick of a song when someone told him the cops were there.

Hundreds of cops awaited the crowd outside of the venue and patrol cars littered the area. Immediately ordered to disperse, the crowd attempted to leave.

But the sheer amount of police officers and vehicles blocking them made it hard to do.

Caldwell recalled police then started knocking tables over and pushing the young attendees around.

Many young artists were jailed that night.

Caldwell felt the artists were being intimidated and the incident could chill the arts community in the area. He felt he had to do something.

So, he reached out to the police captain of that precinct and consistently started attending community meetings — all with the hope of breaking down the misunderstandings between the police and the community.

Reflecting back, Caldwell said, that was the moment that led him to recognize the relevance of community engagement.

For Project Blowed, the incident is a reminder of the importance of standing up for the arts and uplifting and empowering the community.

The group celebrates 26 years of artistic endeavors together this month.

A life and community with art

Caldwell loved to paint and draw as a child. It kept himself busy, allowed him to express his feelings and even helped grow his confidence. For instance, he was overjoyed when he was honored with a blue ribbon award for a portrait.

In his mind, there was no question of the value of the arts in a community. So, about 12 years ago, as he and other artists and community leaders reflected on the vacant buildings being snatched up and developed into luxury homes, they knew they had to do something.

“We were trying to figure out how to deal with, I guess the word is ‘gentrification.’ There were a lot of empty buildings in Leimert,” Caldwell said. “I pitched the idea of doing…galleries in there.”

In the next few months, they created nine pop-up art galleries — “phantom galleries,” as he calls them.

Over time, as more people came to understand the benefits of art and arts programming in the community, and especially for neighborhood youth, support grew.

The Art Walk steadily grew, often drawing hundreds of people, becoming a mainstay in the community and getting regular coverage in local news outlets.

Trauma and healing through art

Then, the pandemic struck.

“This little robot came out of the spaceship and then he made the world stand still for just a day or something, and the world went crazy,” Caldwell said, likening the pandemic to the movie, “The Day the Earth Stood Still.” “Look at us. This is nine months of the world ‘stood still.’”

The Art Walk has been on hiatus since earlier this year, though it held an online event in August.

Still, the pandemic can be an important and fruitful time for painters, filmmakers, storytellers — artists of all kinds.

“As an artist, it has made me dive deeper, and really work out problems that I didn’t know I had until the pandemic happened,” he said.

He said that in some ways, art has been the community’s armor during this difficult time.

“Artists help societies go through…social trauma that events like this cause, as an outlet for that kind of energy, and I think that the African American community is able to kind of wrestle with it because it always has had to deal with this problem,” he said. “They were able to create this armor, which is art. So I think with this particular community, we’ve been through it before, and we use the same armament.”

Community News reporters are enrolled in JOUR 3910 – University Times. They produce stories about under-covered neighborhoods and small cities on the Eastside and South Los Angeles. Please email feedback, corrections and story tips to [email protected].